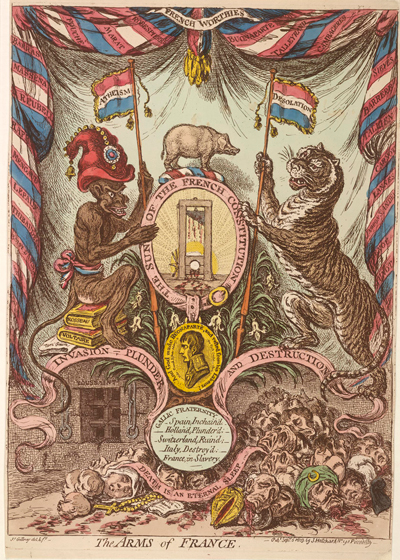

The Arms of France

Coats of arms are by their very nature symbolic. They are intended to represent a country, a region, a city, or a family, and the selection and arrangement of their symbols reflect the values of those entities. So creating a parody coat of arms for France in 1803 gave Gillray an opportunity, using the conventions of heraldry, to distil and satirize, in symbolic form, the foundations and values of France under First Consul, Napoleon Buonaparte.

© Trustees of the British Museum

It was not the first time Gillray had created a heraldic device for satiric purposes. In his largely positive representation of Horatio Nelson in The Hero of the Nile (1798), he couldn't resist puncturing Nelson's heroic facade by providing him with a satiric version of the family crest.

But here in The Arms of France, the effort is much more extensive. The design is bordered by tri-coloured curtains on top and both sides with a comprehensive list of "French Worthies" including Buonaparte, Talleyrand, Sieyès, Cambacérès, Barras, Fouché, Marat, and others—a veritable who's who in French revolutionary political and military circles. At the center of the design, where the heraldic shield would typically appear, embedded in a field of fleur de lis (one of the traditional symbols of France) Gillray places an image of the new and now defining device of revolutionary France—a bloody guillotine backlit by an ambiguously rising or setting sun. The image is surrounded by a "garter" bearing the words, "The Sun of the French Constitution."

Hanging as an appendage to that garter is a golden medallion with the son of the revolution, Buonaparte, engraved upon it with the words, "And God made Buonaparte, and rested from his labours." The traditional divine right sun king has given way to another divinely created son, Buonaparte, recently endorsed by the so-called religious leaders of the country.

Below the medallion, and balanced on the top of the heraldic shield by the traditionally bellicose wild boar, is a white field labeled "Gallic Fraternity." Thanks to the war-mongering Buonaparte, that supposedly revolutionary principle has devolved into dire consequences for the nations unfortunate enough to believe in it:

_Spain, Inchain'd;_

_Holland, Plunder'd;_

_Switzerland, Ruin'd;_

_Italy, Destroy'd;

France, in Slavery.

Along side the central shield showing the guillotine are two heraldic "supporters": a monkey wearing a bonnet-rouge/fool's cap and holding a tri-coloured flag labeled "ATHEISM" and, on the other side, a tiger with a corresponding tri-coloured flag labeled "DESOLATION." As Tim Clayton and Sheila O'Connell have pointed out, the choice of animals illustrates a remark of Voltaire who claimed that the French could be "divided into two species: the one of idle monkeys who mock at everything; and the other of tigers who tear" things apart. The idle (and foolish) monkey sits atop tomes labeled Rosseau (sic) and Voltaire, and a pamplet by Tom Paine. The monkey holds the banner of AETHEISM because all three of those founding fathers of the revolution rejected institutionalized Christianity in favor of a secular humanism. The rampant tiger holds the banner of DESOLATION because, like the wild boar, the tiger is a hunter and attacker which is what France had become under Buonaparte. The ribbon that wraps around the field of Gallic Fraternity and underlies both monkey and tiger sums up France's behavior towards all the countries they pledged to liberate: "Invasion, Plunder, and Destruction."

At the bottom of The Arms of France we see the heraldic "mound" upon which the other elements rest: on the left, the barred window of a prison and on the right and overflowing into the center and left, a bloody collection of heads of Catholic nuns and bishops, Muslim shieks, and numerous other unidentified men, women and children. The name of "Toussaint," the leader of Haitian rebellion against France appears on the prison wall. He had died in French custody on 7 April 1803. A ribbon with the words "Death is an eternal sleep." floats above the severed heads. Usually attributed to Joseph Fouché, Minister of Police under Buonaparte as First Consul, the words were ordered to appear over all French cemeteries instead of any traditional religious mottos, denying the dead of not only a life but an afterlife. This is the reality beneath the heraldry.

As Tim Clayton and Sheila O'Connell have pointed out, Gillray was likely helped and possibly subsidized in this heraldic endeavor by George Canning, the former Under Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs in the first Pitt administration. Gillray's print was not published by Hannah Humphrey, as one would expect, but by John Hatchard who worked with Canning on government propaganda, and it was sold for a price well below the typical market value.

Sources and Reading

- Commentary from the British Museum on The Arms of France.

- Tim Clayton & Sheila O'Connell, Bonaparte and the British, 2015, p. 128.

- Draper Hill, Mr. Gillray The Caricaturist, 1965, o. 109n.

- "Heralds and Coats of Arms," Hand & Lock

- International Heraldry & Heralds

- "Toussaint Louverture," Wikipedia

- "Joseph Fouché," Wikipedia

Comments & Corrections

NOTE: Comments and/or corrections are always appreciated. To make that easier, I have included a form below that you can use. I promise never to share any of the info provided without your express permission.