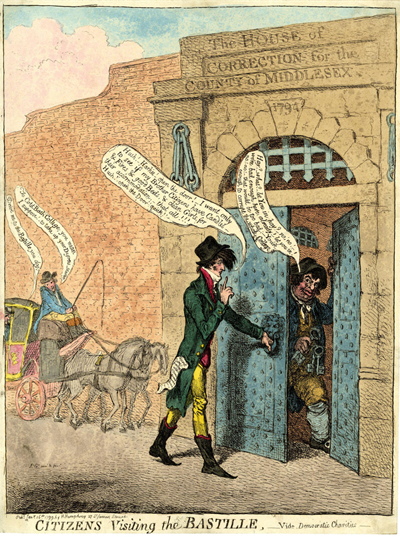

Citizens Visiting the Bastille

The print shows a visit to the House of Corrections for the County of Middlesex, otherwise known as the Coldbath Fields Prison by two Whig Members of Parliament, Sir Francis Burnett (standing before the gate) and John Courtenay (arriving by coach). It was prompted by a debate in Parliament over the question of whether to extend the suspension of habeas corpus which allowed the Pitt administration to arrest and hold individuals suspected of treason and/or sedition without charges and without trial.

© Trustees of the British Museum

A case in point, mentioned in the debate by Mr. Courtenay according to the London Observer, was that of Edward Despard who had been held without trial since 1797 in reportedly deplorable conditions—

in a cell seven feet square dark and damp, with the alternative at that cold season, of either submitting to total darkness, during the twenty-four hours, or admitting all the severity of wind and rain; denied the use of candle-light, deprived of fire, prohibited from seeing his friends, refused the use of pen, ink, or paper, and limited to a bed of 24 inches in width so that he must of course either take the alternative of falling on the stone floor, or lye against the cold benumbing wall. (London Observer, December 23, 1798, p. 4.)

The Tories argued for the continued suspension of habeas corpus, citing the suspected seditious activities of members of the London Corresponding Society including Thomas Evans and Despard and the recently proven cases of Arthur O'Connor and Father James O'Coigley (aka Quigley) who had both been involved in the attempt to orchestrate a French invasion of Ireland to coincide with the Irish uprising of 1798.

The Whigs objected to the continuation of the suspension, citing it as a violation of the fundamental rights of Englishmen and arguing that political detainees whose guilt had not even been tried in court, let alone established, should not be subjected to the same treatment as convicted felons.

Gillray's response is decidedly ambiguous. On the one hand, the Whig Sir Francis is shown as a potential traitor himself with a paper protruding from the pocket of his coat with the words "Secret Correspondence with O'Connor, Evans, Quigley, Despard. . ." And Gillray makes a point of reminding us of Sir Francis' reputation as a playboy, by including among the legitimate concerns of "Candles & Fires, & good Beds, for his incarcerated "brother Citizens" the less savoury request of "Clean Girls for their accommodation." The Gaoler seems to be familiar with Sir Francis'reputation—both political and social—exclaiming "You're enough to corrupt the entire College" (i.e.prison).

But on the other hand Gillray titles his print "Citizens Visiting the Bastille." The Bastille was, of course, the very symbol of the political and social repression of the ancien regime, which the Citizens of the French Revolution were determined to change. Gillray's title, then, invites us to see the House of Corrections for the County of Middlesex as an English version of the hated Bastille. That equivalence is reinforced by the exchange between the passenger in the coach, the Whig MP John Courtenay and the coach driver. Courtenay commands him to "Drive me to the Bastille." The ready reply ("To Cold-Bath-College [i.e. Prison] your mean") suggests that even a common coachman is familiar with the prison's reputation.

Gillray's ambivalence is surprising in one way. Since November of 1797, Gillray had been receiving a stipend from the Pitt government. One would have thought that he would conform to the party line. And it was certainly not part of that line to portray Coldbath Fields as another Bastille. Such remarks, according to the Tory Solicitor General, as reported in the London Lloyd Evening Post (Dec 21, 1798, Page 3)

seemed to have no purpose but that of exciting clamour: it was from a practice to calumniate the proceedings of that House, to assimilate these to the sanguinary measures of Robespierre, and compare our prisons to the Bastille.

But Gillray was never anyone's pet lamb, especially when it came to issues of free speech and thought. As early as 1792 when the King issued a Royal Proclamation Against Seditious Writings and Publications, Gillray responded by publishing Vices Overlook'd in the New Proclamation in which he brutally satirized the King, the Queen, the Prince of Wales, and the Dukes of York and Clarence, including a deeply ironic subtitle addressed to representatives in Parliament:

To the Commons of Great Britain, this representation of Vices, which remain unforbidden by Proclamation, is dedicated, as proper for imitation, and in place of the more dangerous ones of Thinking, Speaking & Writing, now forbidden by Authority.

Here in Citizens Visiting the Bastille, Gilray seems to be attempting to find a middle path between his employers and their adversaries by portraying Sir Francis, as he often does, as a "citizen" of the French Revolution, but at the same declaring the open secret that a political prison like Coldbath Fields is no better than a British Bastille.

Sources and Reading

- Commentary from the British Museum on Citizens Visiting the Bastille.

- "Francis Burdett," Wikipedia

- "John Courtenay (1738-1816)," Wikipedia

- "Edward Despard," Wikipedia

- "Coldbath Fields Prison," Wikipedia

- "Habeas Corpus Suspension Act 1798," Wikipedia

- Thomas Wright and R.H. Evans, Historical and Descriptive Account of the Caricatures of James Gillray #217.

- Thomas Wright and Joseph Grego, The Works of James Gillray, the Caricaturist; With the History of His Life and Times, p. X.

Comments & Corrections

NOTE: Comments and/or corrections are always appreciated. To make that easier, I have included a form below that you can use. I promise never to share any of the info provided without your express permission.