A Birmingham Toast, as Given on the 14th of July

by the Revolution Society

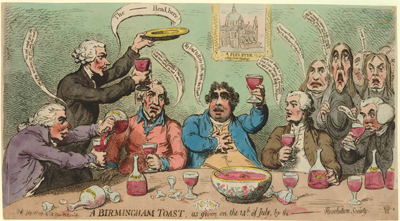

This print purports to show a group of prominent Whigs and their supporters at a banquet in Birmingham celebrating the second anniversary of the fall of the Bastille with a provocative toast.

by the Revolution Society [July 23, 1791]

© Trustees of the British Museum

The Whigs at the table include (from left to right) Richard Brinsley Sheridan (helping himself to another glass of Sherry), Dr. Joseph Priestley, scientist and dissenting minister (proposing the toast), Sir Cecil Wray (famous for parsimony and drinking only small beer) Charles James Fox, leader of the Whigs (at center), Horne Tooke (a politician and perpetual curate of New Brentford), and Theophilus Lindsey (the author of Conversations on Christian Idolatry in the Year 1791, a friend of Priestley, and like him a Unitarian minister. On the wall behind Fox is a picture of St Paul's in London viewed, it is implied, as a Pig Stye by Unitarians such as Priestley and Lindsey. The prayers of the dissenting flock, "Preserve us from Kings & Whores of Babylon!" and "Bring down the Heads of all Tyrants & usurpers quickly good Lord" combine religious zeal with potentially revolutionary political implications.

As Gillray portrays it, the toast is not only provocative, but both treasonous and sacrilegious: treasonous in implicitly wishing for the execution of the King*, and sacriligious in parodying the elevation of the wafers and chalice at the communion service. But, as it turns out, the scene is totally fabricated. None of the Whigs represented in A Birmingham Toast. . . attended the banquet in Birmingham; there was no such incendiary toast. Why would Gillray have produced a print, and a large one at that, which by the time it was published on July 23, 1791, he might have known was false?

To begin to answer that question, it's worth remembering that Gillray's view of the French Revolution had been growing more critical ever since the publication of Burke's Reflections upon the Revolution in France in 1790. His portrayals of Dissenters such as Dr. Price in Smelling Out a Rat (December, 1790) had become more openly hostile and his portrayals of Burke in The Impeachment, or the Father of the Gang, Turn'd King's Evidence in May of 1791 decidedly more sympathetic. And with the recent arrests of the King and Queen of France while attempting to flee the country, and the debates in the National Assembly over the place of monarchy in the new constitution, it must have seemed to Gillray that all of Burke's predictions were being realized. The sense of chaos now being unleashed would have been reinforced by the terrible events following the banquet in Birmingham which were both known and fresh in people's minds by the time Gillray's companion prints The Hopes of the Party Prior to July 14th (July 19) and A Birmingham Toast (July 23) were published.

Here's what happened. As the second anniversary (July 14, 1791) of the fall of the Bastille approached, banquets were planned in both London and Birmingam to celebrate the occasion. The London banquet was to be held at the famous Crown and Anchor Tavern; the corresponding Birmingham meeting was planned for Dadley's Hotel (sometimes called the Royal Hotel) in the center of Birmingham. In both places, there were signs of trouble brewing as the occasion drew nearer. In London, the upcoming meeting was described "illegal and unconstitutional," and poems and parodies satirizing the meeting and its proponents began to appear in the London Times and the Evening Mail. In Birmingham, where there was long-standing tension between the Church and King crowd who supported the Tories and Church of England and the Dissenters like Priestley who wished to repeal the restrictive Test and Corporation acts, the announcement of the "French Revolution Dinner" in the local Birmingham newspaper was followed by the ominous note that a complete list of attendees would be published afterward. And by the morning of the meeting, graffiti had been scrawled on the walls of various buildings declaring "Church and King for ever," and "destruction to the Presbyterians."

Not suprisingly, in both London and Birmingham the best known and most controversial Whigs decided not to attend. Those included Fox, Sheridan, and Lord Stanhope in London, and Priestley in Birmingham. As the Morning Post and Daily Advertiser put it in their July 13 issue,

The scandalous pains taken by the Ministerialists [i.e. Tories] to make a Riot at the Anniversary of the French Revolution on Thursday, after predicting that it would take place, have constituted the chief argument with Messrs Fox, Sheridan, and others, of just but temperate principles of Freedom, to stay away;—that if the Treasury dependents should succeed in creating a Riot, they should at least be defeated in the plea of imputing it to [the] Opposition.

It appears that the only character in Gillray's print to celebrate the occasion was Sir Cecil Wray and it was NOT the Birmingham meeting, but the one held at the Crown and Anchor Tavern in London where he was listed as a Steward. Nonetheless, approximately 1000 persons attended the London meeting and approximately 80-90 in Birmingham. Both meetings were purposely concluded early to avoid confrontation and none of the attendees appears to have been assaulted.

But in Birmingham crowds began to gather in front of Dadley's hotel in the evening, in spite of the fact that most of the meeting attendees had already dispersed. Windows were broken and the furniture in the meeting room damaged. But being reminded that Dadley, the hotel proprietor, was a Churchman, the angry crowd moved on to attack and set fire to Priestley's chapel, the New Meeting House, in Moor Street along with its considerable library of theological books until nothing was left "but the four blackened outside walls." Then they destroyed the other Unitarian chapel, the Old Meeting House, before moving on to Priestley's house itself.

The depradation that began that evening continued for three days from July 14th to July 17th, and when all was said and done, four dissenting chapels had been virtually destroyed and twenty-seven houses had been attacked, most of which belonged to dissenters. Although none of the dissenters lost their lives, there were a number of deaths among the rioters, crushed by collapsing walls or trapped in the wine cellars of burning houses.

Although it now seems likely that most of the objects of attack had been targeted in advance and were prompted by long-simmering resentments within the Birmingham community, there were rumors in Birmingham and London, persistent enough to warrant contradiction that the proximate cause of the riots was a toast by Priestley. In the European Magazine and London Review, for instance, the following Note appeared dated Lancaster, July 17th:

An injurious report having been spread that an obnoxious toast, given by Dr. Priestley at the Hotel Meeting in Birmingham, on the 14th inst. was what instigated the mob to destroy his house, etc. I do hereby declare that I spent the day with him, from nine in the morning till five in the afternoon; that he was not at the Hotel or any other public meeting; that I dined with him at his own house, where the whole company was—himself, Mrs. Priestley, my wife, son, daughter, and myself.

A. Walker

Lecturer in Philosophy

Other newspapers and magazines, including the Gentleman's Magazine and Historical Chronicle and the Political Magazine though not explicitly defending Priestley, made a point of reporting all the toasts proposed throughout the evening (there were twenty-one of them) as if to set the record straight.

Given a political climate which was becoming increasingly polarized and vindictive and where rumors circulated freely, I would suggest that Gillray, already alarmed by by events at home and abroad, took advantage of a clearly well-circulated rumor to attack what he perceived as revolutionary tendencies by giving that rumor potently graphic form.

* The Lewis Walpole Library Library has an alternative version of the finished print with a speech bubble for Priestly that removes the dash and replaces it with "King's" so that the bubble reads: "The King's Head, here." The replacement looks to have been a crude later addition in a slightly different script, so it is unlikely to have been produced by Gillray himself. But it only makes explicit what Gillray and Fores surely intended.

Sources and Reading

- Commentary from the British Museum on A Birmingham Toast, as Given on the 14th of July, by the Revolution Society.

- Old and New Birmingham: A History of the Town and Its People

- "Priestley Riots," Wikipedia

- "Joseph Priestley," Wikipedia

- "Sir Cecil Wray, 13th Baronet," Wikipedia

- "John Horne Tooke," Wikipedia

- "Theophilus Lindsey" Wikipedia

- "Revolution Society," Wikipedia

- Thomas Wright and R.H. Evans, Historical and Descriptive Account of the Caricatures of James Gillray #58.

- Thomas Wright and Joseph Grego, The Works of James Gillray, the Caricaturist; With the History of His Life and Times p. 131.

Comments & Corrections

NOTE: Comments and/or corrections are always appreciated. To make that easier, I have included a form below that you can use. I promise never to share any of the info provided without your express permission.