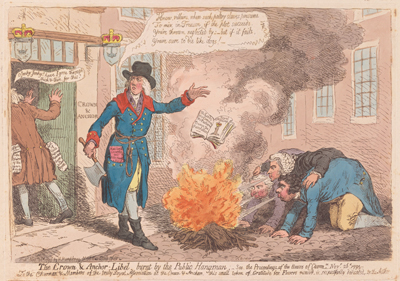

The Crown and Anchor Libel Burnt by the Public Hangman

Perhaps the first thing to know about The Crown and Anchor Libel Burnt by the Public Hangman is that it is almost certainly misdated. The print includes a publication date of November 28th and it references the Parliamentary debate a few days earlier over an ultra-conservative pamphlet called Thoughts on the English Government written by John Reeves, the founder of the organization popularly known as the Crown and Anchor Society. Going far beyond what Pitt or almost any other Tory would have argued, Reeves asserted that

the government of England is a monarchy; the monarchy is the ancient stock from which have sprung those goodly branches of the legislature, the Lords and Commons, that at the same time give ornament to the tree, and afford shelter to those who seek protection under it. But these are still only branches, and derive their origin and their nutriment from their common parent; they may be lopped off, and the tree is a tree still; shorn, indeed, of its honours, but not like them, cast into the fire. The kingly government may go on in all its functions, without Lords or Commons, it has heretofore done so for years together, and in our times it does so during every recess of parliament; but without the king, his parliament is no more. The king, therefore, alone it is who necessarily subsists without change or diminution; and from him alone we unceasingly derive the protection of law and government.

© Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

Not surprisingly, the reading of this passage during the debate on the Treasonable Practices and Sedition Acts provoked consternation among the Whigs, who immediately branded the passage as "a libel upon the House of Commons," and embarassment among the Tories who had been providing not so secret support for Reeves's activities against radical politicians and groups such as the London Corresponding Society. After trying in vain to shelve the discussion of Reeves's pamphlet to save face, Pitt was, in effect, forced to denounce the publication and distance himself from Reeves. All of this played out over more than a few days. And it was not until December 14th that Richard Brinsley Sheridan presented the motion that, I believe, represents the true origin of Gillray's print.

On that day, he proposed that Reeves be brought before the House of Commons and formally reprimanded by the Speaker for his libel against the House; and furthermore that

one of the said printed books be burnt by the hands of the common hangman in the New Palace Yard, Westminster, on Monday, the 21st day of this instant December, at one of the clock in the afternoon.

If, as it seems likely, this is indeed the origin of Gillray's striking image of Reeves's book being burned by Pitt appearing as the "public hangman," the print could not have been published any earlier than mid-December. But though the publication date may have been fudged, the print remains nonetheless a wonderful example of Gillray's ability to take contemporary situations and events and create from them brilliant multi-layered satires.

The first object of that satire is, of course, William Pitt, who must have cringed in seeing himself portrayed as the "public hangman" exacting the very retribution called for by the Whigs. Tossing into the fire Gillray's version of Reeves's offending pamphlet with a prominent image of the "Royal Stump; and the inscription, "No Lords No Commons No Parliament," Pitt carries in his pocket a book whose title provides an apt comment on the loyalty of Prime Ministers: "Ministerial Sincerity and Attachment, A Novel." That criticism is further reinforced by lines from Joseph Addision's Cato: A Tragedy (Act Three, Scene 6).

Know, villains, when such paltry slaves presume

To mix in Treason, if the plot succeeds,

You're thrown neglected by: - but if it fails,

You're sure to die like dogs!"

In Gillray's print the lines are spoken by Pitt and would seem to represent a stern reprimand of Reeve's behavior. But as Gillray's audience would have known, the lines in Addison's play are spoken by the double-dealing Sempronius who first betrays Cato and then the other leaders of the mutiny against Cato, ultimately pursuing only his own self interest.

The second target of Gillray's satire is John Reeves who is exposed as a government hireling retreating back to the Crown and Anchor complaining to his immediate boss, "Jenky," (Lord Hawkebury) of his mistreatment while carrying papers in his pockets, which identify that he has been receiving "£400 pr Ann," for maintaining a "List of Spies Informers Reporters [and] Crown & Anchor Agents."

The third, though less explicit target, of Gillray's satire is the trio of Whigs—Sheridan, Erskine, and Fox— who had been the principal Whig representatives in the "libel" debate. Their posture in Gillray's print is anything but upright, affected no doubt by finding themselves, the self-professed guardians of English liberty and freedom of speech, assisting at a book burning.

Sources and Reading

- Commentary from the British Museum on The Crown and Anchor Libel Burnt by the Public Hangman.

- Draper Hill, Mr. Gillray The Caricaturist, 1965, p. 55

- "John Reeves (activist)," Wikipedia

- "Association for Preserving Liberty and Property against Republicans and Levellers," Wikipedia

- "Charles Jenkinson, 1st Earl of Liverpool," Wikipedia

- A.V. Beedell, "John Reeve's Prosecution for a Seditious Libel 1795-6: A Study in Political Cynicism," The Historical Journal, 36 4 (19930, pp. 799-824.

- Thomas Wright and R.H. Evans, Historical and Descriptive Account of the Caricatures of James Gillray #139.

- Thomas Wright and Joseph Grego, The Works of James Gillray, the Caricaturist; With the History of His Life and Times p. 194-195.

Comments & Corrections

NOTE: Comments and/or corrections are always appreciated. To make that easier, I have included a form below that you can use. I promise never to share any of the info provided without your express permission.