The Giant Factotum Amusing Himself

The Giant Factotum shows Prime Minister, William Pitt, towering over the other members of the House of Commons, both Tory and Whig. His pockets are stuffed: on one side with gold coins labeled "Resources for supporting the War;" on the other with scrolls representing military resources for the same purpose—200,000 Seaman, 150,000 Regulars, Volunteers, and Militia.

© Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

On the Ministry side of the House, the colossal Pitt is adored and supported by his Tory followers, among them a fawning George Canning who kisses his foot as if he were a king, the burly Scot, Henry Dundas, Secretary of State for War, and William Wilberforce, the spokesman for the abolition of the slave trade. On the Opposition side, the diminutive Michael Angelo Taylor and the the entire opposition benches recoil with horror and dismay as Pitt's giant foot crushes the Whig leaders Charles James Fox and Richard Brinsley Sheridan, the famous Whig lawyer Thomas Erskine, and the young reformer Charles Grey.

The word "factotum" derives from two Latin words: "facere" meaning to do, and "totum" meaning all or everything. In this case, it suggests someone who can "do it all." In January 1797, that must have seemed an accurate assessment of Pitt. In spite of the fact that Britain and the First Coalition countries had been largely unsuccessful in their fight against French revolutionary forces in 1796, British citizens and the members of Parliament were still solidly behind the King and Pitt in rejecting France's humiliating peace proposals at the end of the year. And even moreso when Pitt's persistent warnings of an imminent French invasion (ridiculed and discounted by the Whigs) were shown to be remarkably prescient by the spectacular (failed) attempt by a French fleet of 44 ships and nearly 20,000 men to gain a foothold in Ireland as a prelude to an attack on Britain.

But as in so many prints created by Gillray, the satire cuts more than one way. The Whigs may be pathetic; the Tories, subservient. But Pitt is portrayed as supremely arrogant and self-absorbed, acknowledging neither the reverence of his followers nor the destruction of his opponents—simply amusing himself. It is no accident that the ceremonial mace, the symbol of the power of the Commons, lays unobserved and unattended on the floor. Nor that in a gesture of supreme potency, Pitt is shown straddling the Speaker's chair so that the royal coat of arms occupies the space where his genitals would be: the House of Commons—c'est moi.

Pitt is "amusing himself" with a version of the child's game, cup and ball. But in this case, the ball is the world where France's conquests have given it a formidable presence. And Pitt has chosen to play the much harder, spike and ball version of the game, most popular in France, called the bilboquet. The string of his toy looks to have been broken at least once, posing a further challenge to his possibilities of success.

© Collector's Weekly

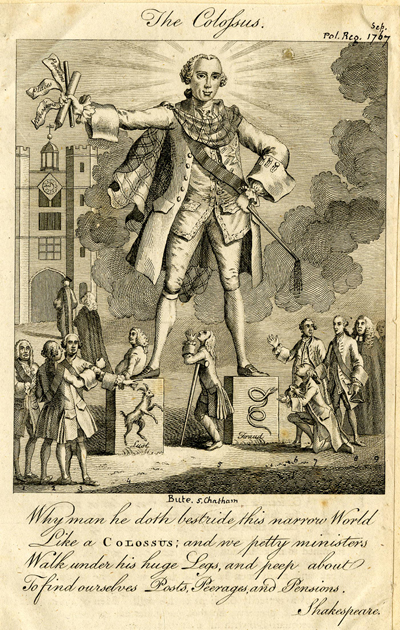

In creating The Giant Factotum Gillray may have remembered an earlier portrait of another dominating figure on the British political scene, Lord Bute, George III's earliest mentor and the rumored lover of the dowager queen. The outstretched right arm, the left arm akimbo, the outsized proportions of the figure—all bear some resemblance to Gillray's print. But if the resemblance was intended as an allusion, it is once again deeply ambiguous. If Gillray were trying to flatter Pitt at this moment in January (he received a stipend from Pitt through Canning in November), he couldn't have chosen a better allusion to suggest how far Pitt had exceeded expectations. The "petty minister" looking up imploringly between Bute's colossal legs is none other than the Earl of Chatham, Pitt's father. But if Gillray were illustrating the dangers of the younger Pitt's overweening ambition, Bute could also serve. The Shakespearean quotation beneath the image is from Julius Caesar.

The Colossus

[September, 1767]

© Trustees of the British Museum

Sources and Reading

- Commentary from the British Museum on The Giant Factotum Amusing Himself.

- Draper Hill, Mr. Gillray The Caricaturist, 1965, p. 63n

- Draper Hill, Fashionable Contrasts, 1966, #22

- "John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute," Wikipedia

- "William Pitt the Younger," Wikipedia

- "Cup-and-ball," Wikipedia

- Thomas Wright and R.H. Evans, Historical and Descriptive Account of the Caricatures of James Gillray #160

- Thomas Wright and Joseph Grego, The Works of James Gillray, the Caricaturist; With the History of His Life and Times, pp.216-217.

Comments & Corrections

NOTE: Comments and/or corrections are always appreciated. To make that easier, I have included a form below that you can use. I promise never to share any of the info provided without your express permission.