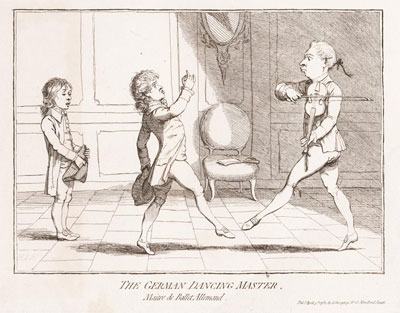

The German Dancing Master. Maitre de Ballet Allemand

This is one of two prints from circa 1781/82 featuring foreign dancing masters and their awkward English students. The other is Regardez Moi, which shows Earl Cholmondeley being instructed by the famous French dancer Gaetan Vestris.

[April 5, 1782]

© Lewsis Walpole Library, Yale University

In this case, the dancing master is German, and, according to the British Museum, his name is Jansen (or, in other accounts, Janson). I have looked in vain for information about him in contemporary newspapers where one would expect to find at least advertisements of his services, notices of his attendance at high society functions, or a final obituary. But the pitifully little I have discovered about him is incidental to more extensive accounts of his progeny: his daughter Therese Jansen Bartolozzi, a pianist (~1770-1843), his son, Louis Jansen, a composer (1774-1840), and his granddaughter, Madame Vestris, a singer/actress, producer, and manager (1797-1856).

Both his children were born in Aachen Germany (aka Aix-la-Chapelle) where M. Jansen seems to have established himself as "the first dancing master of his age." But at some point before 1782, he moved to London, brought there, according to one account, by Earl Spencer and Lord Mulgrave. The move seems to have put Jansen and his children into immediate contact with the rich and famous of London in the 1780s, especially in the arts. Both Louis and Therese Jansen took lessons from Muzio Clementi, the virtuoso Italian pianist, composer, and conductor. Therese, it is said, became one of Clementi's star pupils, and in the 1790s was the dedicatee of piano pieces by Clementi, Jan Dussek, and Joseph Haydn. Louis was also precocious, in his case as a composer, publishing three piano-sonatas (Op. 1) and eighteen "favorite" minuets in 1793 at the age of ninteen.

Initially, however, the careers of both his children seem to have been subordinated to the family dance business. According to the anonymous biography of Madame Vestris, soon after Jansen senior's arrival in London,

Miss Jansen likewise. . .began teaching that beautiful and graceful art. Several of the very highest families benefitted by her instructions, and she was eminently successful; so much so, indeed, that she and her brother, Mr. L. Jansen (who taught dancing only because he was bred to it by parental authority-music being his decided forte), realized rather more than two thousand pounds per annum. (p. 4)

Until the 1790s, the Jansens' income from dance seems to have been more than sufficient, which may explain why there are no contemporary advertisements of concerts featuring Jansen's daughter.

Miss Janson was one of the most noted performers on the pianoforte, but her father's income being sufficient, she, during his life, had no occasion to make use of her abilities further than to contribute to the amusement of her father's guests, who were people of the highest rank and fashion. Many costly entertainments were given by old Mr. Janson; but this extravagant expenditure of his income at length brought him into difficulties. (pp. 4-5)

By 1795, when Therese was engaged to be married to Gaetano Bartolozzi, the son of the famous engraver, the affairs of M. Jansen were in such disarray that he was unable to pay the £100 that he had promised his daughter. And it was only through a loan from a rich friend of her brother Louis that Miss Janson was able to proceed with the marriage.

Louis seems to have followed in his father's footsteps in more ways than one.

He made his first entree in London as a musician when quite a young man, and with the brightest prospects. When in the zenith of his prosperity he kept his own carriage—the best of society—and frequently had the honour of dining with his late Majesty George IV, when Prince of Wales.

But, according to his obituary in the Gentleman's Magazine for 1840 (quoted by Tom Moore), Louis fell victim of his own extravagance and dissipation, dying "in one of those abodes for the destitute, situate in Northumberland-street, Marylebone."

There is a long tradition of satiric prints about dancing masters, usually presenting them as French and foppish, and their clients as awkward and foolish. And though this is a German dancing master, the French subtitle of Gillray's print still preserves a minimal connection with that tradition. But as in Regardez Moi, I suspect that making fun of dancers and their clients is not (or not the only) point of the print.

Gillray never does anything without a reason. And it is clear that he wants us to notice the empty chair with the open book resting upon the seat. The outstretched legs of Jansen and his student form a V-shaped container for the chair. And on the back wall the mirror and wall sconce seem to point down to it. If this were just a decorative chair or the representation of how Jansen's studio appeared, Gillray could easily have set the second student on, or before, the chair, awaiting his turn with the master. But he doesn't.

At this point, I would love to be able to explain what Gillray is really up to. But I can't. There is scacely a mention of Jansen the dancing master at all between 1770 and 1783. But I CAN suggest that others were probably in the know. There is an anonymous portait caricature published by Thomas Cornell around the same time as Gillray's that resembles the figure in The German Dancing Master. If this is indeed Jansen, it suggests that the society dancing master had now achieved sufficient notoriety that two printsellers thought they could make money off of it.

© Trustees of the British Museum

Sources and Reading

- Commentary from the British Museum on The German Dancing Master. Maitre de Ballet Allemand.

- "Therese Jansen Bartolozzi," Wikipedia

- Katelyn Clark, "The London Pianist: Theresa Jansen and the English Works of Haydn, Dusseck, and Clementi," HAYDN: Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America: Vol. 2 : No. 1 , Article 2

- Tom Moore, The Collections of Favorite Airs or Melodies of Louis Jansen

- Oliver Strunk, "Notes on a Haydn Autograph," The Musical Quarterly 1934, Vol. 20, No. 2 (Apr., 1934), pp. 192-205

- "Muzio Clementi," Wikipedia

- Anonymous, Memoirs of the Life, Public and Private adventures of Madame Vestris pp. 4-5.

- "Lucia Elizabeth Vestris," Wikipedia

- Thomas Wright and R.H. Evans, Historical and Descriptive Account of the Caricatures of James Gillray #369.

- Thomas Wright and Joseph Grego, The Works of James Gillray, the Caricaturist; With the History of His Life and Times, p. 34.

Comments & Corrections

NOTE: Comments and/or corrections are always appreciated. To make that easier, I have included a form below that you can use. I promise never to share any of the info provided without your express permission.