A French Hail Storm. . .

At the start of the French Revolutionary War, the British navy, like Britain in general, assumed that the war would be short-lived and that the revolutionaries would be defeated by their own internal dissension. So the naval approach was generally conservative concerned with preserving British trade and containing the French by blockading their principal ports, attacking only if they attempted to land or leave.

In February 1793, the 66-year old Richard Howe was named Admiral of the Channel Fleet and (among other responsibilities) was tasked with monitoring the major French port at Brest. But in mid-November, a large fleet of French ships homeward bound with supplies from America was sighted, chased, and then lost in a fog, slipping past the blockade untouched while the bulk of the British fleet was returning to their home base at Torbay. The disappointment and embarrassment to the Pitt administration were made even greater by initial (and ultimately false) reports of Howe capturing as many as five French ships of the line in the encounter.

© Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University

Contemporary newspapers had a field day with the episode, assuring the families of Howe's sailors that they should never have to worry about their sons in battle since Howe would never engage the enemy, and portraying Howe's oversight as a kind of self-serving slumber.

Peaceful slumb'ring o'er the Ocean,

Lord Howe fears no Frenchmen nigh;

The winds and waves in dangling motion

Rock him with their Lullaby.

Chorus

Lullaby, lullaby, lullaby, now they fly,

Lord Howe fears no Frenchmen nigh.

Is the wind North East yet blowing

Still no Frenchmen he'll decry;

The lucky fog its boon bestowing,

Puts its finger in his eye

Chorus

Lullaby, lullaby, lullaby, in his eye,

Lord Howe sees no Frenchmen nigh.

(December 19th, 1793 Morning Post.)

But unlike the contemporary newspapers, Gillray's print takes the critique in a very different direction, suggesting that Howe was not simply cautious or negligent, but bought off by French gold. Howe is shown as Neptune, god of the sea, standing with a trident in a scallop-shell chariot a la Venus drawn by dolphins towards Torbay. He is being pelted by a hail-storm of French coins issuing from cherubs with revolutionary bonnet rouges. The coins tear a hole in the British flag attached to Howe's trident and prevent him from seeing the French fleet gliding toward the port and Chateau of Brest in the distance. It does not, however, prevent him from gathering up the skirts of his coat the better to catch the coins.

As the reference to the American war in Howe's speech bubble suggests ("Ah! it was just such another cursed peppering as this, that I fell inn with, on the coast of America in the last War" Gillray's critique has its origins in suggestions made at the time (1777) that the porousness of Howe's American blockade was financially motivated, that it was (at least in part) prompted by a desire to extend a war that was proving so profitable to Howe and his army brother, General, Sir William Howe.

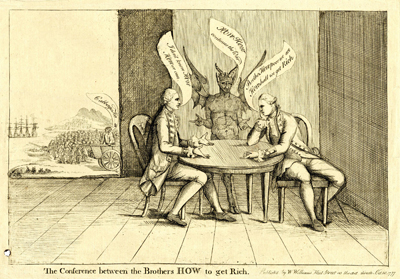

The Conference between the Brothers How to get Rich

[October 10, 1777]

© Trustees of the British Museum

In The Conference between the Brothers How to get Rich, for instance, Sir William asks his brother Richard "How shall we get rich?" The devil between them provides the answer: ". . .continue the War."

Sources and Reading

- Commentary from the British Museum on A French Hail Storm. . ..

- "Richard Howe, 1st Earl Howe," Wikipedia

- "Neptune (mythology)," Wikipedia

- "Brest, France," Wikipedia

- "History of Torquay," Wikipedia

- Robert Harvey, The War of Wars, London, 2006

- Thomas Wright and R.H. Evans, Historical and Descriptive Account of the Caricatures of James Gillray #109.

- Thomas Wright and Joseph Grego, The Works of James Gillray, the Caricaturist; With the History of His Life and Times, p. 175.

Comments & Corrections

NOTE: Comments and/or corrections are always appreciated. To make that easier, I have included a form below that you can use. I promise never to share any of the info provided without your express permission.