Homer Singing his Verses to the Greeks

This print features the singer/songwriter Captain Charles Morris (1745 - 1838) in tattered dress singing one of his creations to a table of sympathetic Whig listeners including Richard Brinsley Sheridan and, possibly, Michael Angelo Taylor* (on the far side of the table) and Charles James Fox (on the near side).

© Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

After returning from military service in the American war (hence the Captain), Morris was part of the gambling, drinking, and whoring crowd that surrounded the Prince of Wales in the 1780s and '90s. Inheriting a gift for song and rhyme from his father, Captain Morris made a sometimes precarious living composing and performing his catchy songs in praise of drink, sex, and the city. And like most members of the Prince's set, he was in and out of debt with some frequency. But such was his popularity with the Prince, the Captain was eventually provided with an annuity of £200 per year. Not surprisingly for someone attached to the Prince of Wales, he was a loyal Whig and friend of Fox and Sheridan. And when Whig meetings were held, such as the celebration of Fox's birthday, Captain Morris was regularly called upon to use his talents to provide entertainment in the form of satiric songs against Pitt and the Tories.

But his most famous creation was the one alluded to in this print, "The Plenipotentiary." a thoroughly bawdy song which, like Gillray's Presentation of the Mahometan Credentials. . . celebrated the supposedly outsized "credentials" of the Turkish Plenipotentiary. Here's a sample:

When to England he came, with his prick all aflame,

He showed it his hostess on landing,

Who spread its renown thru all parts of the town,

As a pintle past all understanding.

So much there was said of its snout and its head,

That they called it the great Janissary,

Not a lady could sleep till she got a sly peep,

At the great Plenipotentiary.

There are at least two frames through which to view this print: one provided by the title, Homer Singing his Verses to the Greeks and the other through the quotation from Shakespeare's Henry IV Pt. 1 in Fox's request: "Come sing me a bawdy song, to make me merry."

Viewed through the first frame, the print is a travesty, mocking how far we have fallen from the celebration of heroic virtues by Homer in the verses of the Odyssey and the Iliad. Homer is now a bawdy balladeer and the Greeks are a bunch of gamblers and card sharks.

Viewed through the second frame provided by the allusion to Shakespeare (III.iii.l3-14), the ":Greeks" around the table do not fare any better. Fox, is the world-weary Falstaff and Sheridan is the drink-addicted, fiery-nosed Bardolph. The full set of exchanges between Falstafff and Bardolph from which Fox's words are excerpted is a brilliant (and accurate) supposition by Gillray of Fox's own mood swings after the recent defeat of the Grey's Reform Bill.

Falstaff:

Bardolph, am I not fallen away vilely since this last action? Do I not bate? Do I not dwindle? Why, my skin hangs about me like an like an old lady's loose gown. I am withered like an old applejohn.

Bardolph:

Sir John, you are so fretful you cannot live long.

Falstaff:

Why, there is it. Come sing me a bawdy song, make me merry. I was as virtuously given as a gentleman need to be, virtuous enough: swore little; diced not above seven times – a week; went to a bawdy house once in a quarter – of an hour; paid money that I borrowed, three or four times; lived well and in good compass; and now I live out of all order, out of all compass.

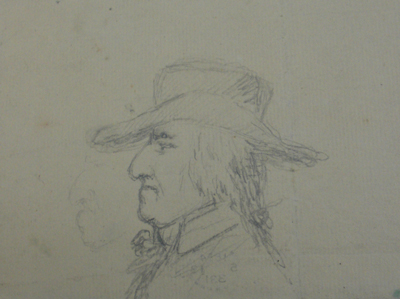

Homer Singing his Verses to the Greeks is inscribed "Js Gy ad vivam fect" In Gillray's work, this does NOT mean that he observed Morris performing for Fox and Sheridan at a table like this. It usually means that he has created the main subject of his caricature from a sketch made (usually on small card stock) from life. And in this case, I think we can point to the sketch which is the basis of the print among the untitled and currently unidentified drawings by Gillray in the British Museum.

Author's Photo

© Trustees of the British Museum

The unusually shaped hat, the hair scruffy but covering his ear, the collar of his jacket, and the neckerchief tied in front—all suggest that this is Captain Wallace. But the Captain Wallace of the print has a protruding lower lip and an even more curved nose. The sketch seems more like a portrait than a caricature. But if you look closely at the drawing, to the left of the main profile (or click on the link below the thumbnail), you can see that Gillray is in fact trying out the curved nose and protruding lip that we see in the print. This suggests, I believe, that at least at this period of his life, Gillray may have started with a more or less acccurate sketch of his potential subject taken from life, and then exaggerated the features (as needed) for the final print.

There are at least three versions of this print which differ mainly in the words attributed to Fox. In the version at the Beinecke Library which is most likely the orginal, Fox says "Come sing me a Bawdy Song, to make me Merry," correctly quoting Falstaff from Henry IV Part 1. In the second version in the British Museum (#1868,0808.6643), the word "Boosey" has been substituted for "Bawdy." But there is evidence of burnishing in the slightly darkened background behind "Boosey" that makes it likely that this was a later version. In addition a small piece of paper is attached to the print announcing

Also published this morning,

The Fourth Edition of SONGS,

by Capt. Morris Enlarged and corrected. Price 2s.

This paper was almost certainly snipped from The London World Fashionable Advertiser from May 1st 1787 p. 2. where the advertisement appears exactly as shown in this British Museum version. See below:

![]()

The snippet must have been cut from the 1787 paper and then attached to the print some time after 1797.

Finally, there is a third version, also in the British Museum (#1851,0901.877), which attempts to replace "Bawdy" or "Boosey" with "Bold." But in this case, the editing job was even worse. The word "Bold" has fewer letters than "Bawdy" leaving an awkward space where a faint, white "y" still appears.

My guess is that both Brtitish Museum prints are late productions, burnished and edited at a time when explicitly "Bawdy" Songs were no longer acceptable in polite society. Indeed the progression from "Bawdy" to "Boosey" to "Bold" may be taken as a perfect example of the changes in society that doomed Gillray's reputation as a whole.

* The diminutive Taylor had appeared next to Sheridan in a similarly convivial setting in The Feast of Reason, & the Flow of Soul. . . in February.

Sources and Reading

- Commentary from the British Museum on Homer Singing his Verses to the Greeks.

- "Morris, Charles," Wikisource

- Lyra Urbanica the Social Effusions of Charles Morris

- Vic Gatrell, "Chapter 10: The Tree of Life," City of Laughter, 2006, pp. 295-300

- Kate Horgan, The Politics of Songs in Eighteenth-Century Britain, 1723–1795, 2016.

- Thomas Wright and R.H. Evans, Historical and Descriptive Account of the Caricatures of James Gillray #441

- Thomas Wright and Joseph Grego, The Works of James Gillray, the Caricaturist; With the History of His Life and Times p. 222.

Comments & Corrections

NOTE: Comments and/or corrections are always appreciated. To make that easier, I have included a form below that you can use. I promise never to share any of the info provided without your express permission.