Lilliputian-Substitutes, Equiping for Public Service

This is one of at least two prints by Gillray dealing with the resignation of Prime Minister William Pitt over the issue of Catholic Emancipation and the subsequent change of administration. The first print, Integrity Retiring from Office (Feb. 24, 1801), showed Pitt (and some of the outgoing administration) departing through the Treasury Gate. Lilliputian-Substitutes focuses on members of the incoming Addington administration as they prepare to take office.

In the first part of his popular satire, Gulliver's Travels, Jonathan Swift uses size as a satiric device for exposing the outsized pretentions of the tiny Lilliputians whose inhabitants are not more than six inches high but whose vanity is not limited by their size. In Lilliputian-Substitutes, Equiping for Public Service, Gillray alludes to Swift's Travels and uses stature in a similar fashion to satirize the members of the new administration as they attempt to assume the roles and trappings of their (figuratively) much larger predecessors.

© Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

When rumors of Pitt's decision to resign began circulating at the beginning of February, there was both disbelief and confusion: disbelief that the rumors could be true, and confusion about what it meant. Did Pitt actually resign or was he removed? If the latter, did his removal suggest a change of policy and direction? Who would be the beneficiary of such a change? An item in the Morning Post and Gazetteer for February 9, 1801 articulated one theory.

Upon the resignation or removal of Mr. PITT, people will naturally turn their eyes to one man who has long been the object of their affections. Need we say who that man is? That no one but Mr. Fox could save the country, we will not assert; but if the country is to be saved, it must be, to use the language of Mr. Sheridan, by following the advice of Mr. Fox.

A few sentences later, the same note suggests the "rumour, that Mr. ADDINGTON will succeed Mr. PITT, is by no means probable."

As that rumor grew stronger and was eventually confirmed, however, there was a second phase of disbelief and disappointment. On the Tory side, there was amazement that Addington would consider himself capable of succeeding Pitt. Lady Malmesbury (quoted in Robin Reilly) described Addington's selection as "a farce." And George Rose, Pitt's longtime colleague at the Treasury, was equally dismayed.

To what length will Vanity not carry a Man? amiable and good in private life. . . [Addington] is no more equal to what he has undertaken than a child. (Quoted by Reilly, p. 387)

On the Whig side, the disappointment was not only that Fox was unlikely to succeed Pitt, but that the change of administration, they feared, would not bring a change of policy; that the same strong arm measures championed by Pitt would be continued by Addington. This fear was best expressed by Fox himself at a meeting of the Whig Club as reported in the May Monthly Mirror (May 1, 1801).

At a meeting of the Whig Club on Tuesday, Mr. Fox, adverting to the late change in the ministry, lamented that it had not produced any change in the politics of the government, or the house of commons; and he apprehended, from the extraordinary acquiescence of the country, that the story of the king who threatened to send one of his jack-boots to govern as his proxy would not only be realized, but that even the jack-boot of the jack-boot would be supported by parliament.

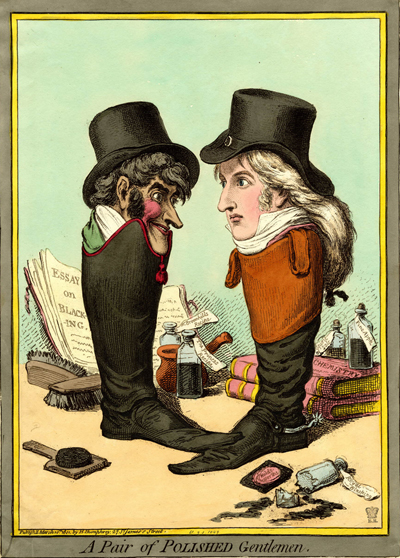

As the editors of London und Paris first pointed out, Fox's witticism was the likely starting point for Gillray's satire. Addington, as Prime Minister, is shown as Pitt's jack-boot standing on the Treasury Bench, virtually overwhemed by the tri-corn hat and Windsor coat of the former prime minister. In A Pair of Polished Gentlemen published in March, Gillray had already merged a person with his boots, so when he heard of Fox's expression, he must have known immediately how he could portray Addington.

© Trustees of the British Museum

But it was the generally low opinion of the new administration reflected in remarks such as Lady Malmesbury's and George Rose's that must have prompted Gillray to portray Addington and his minions as midgets or children playing dress up in their parent's clothes. The new Chancellor, the Earl of Eldon, for instance, sits on the woolsack his legs not long enough for his feet to reach the ground while his predecessor's (Loughborough's) wig flows beyond his feet and trails onto the ground. Appropriately, his speech,

O such a Day as This, so renown'd, so victorious

Such a Day as This, was never seen.

is actually derived from one of the songs from the The Comic Opera of Tom Thumb the Great, the diminutive English folk hero. The rest of the verse, sung by Doodle is as follows.

SURE such a day,

So renown'd, so victorious,

Such a day as this was never seen.

Courtiers so gay,

And the mob so uproarious;

Nature seems to wear an universal grin.

In front, next to Addington, is Lord Hawkesbury, who is trying in vain to fill the capacious breeches of William Grenville, Pitt's Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs and a hawk vis a vis France. See Gillray's A Keen-Sighted Politician Warming His Imagination for the breeches he would have to fill. Hawkesbury naturally wonders whether he can keep those breeches up in his "March to Paris" or whether in making concesions to France that might (and in fact later did) result in peace he might be viewed as a crypto sans-culotte.

In the center of the print, Lord Hobart is similarly dwarfed by the Scottish tartan breeches, tam o' shanter, and the huge Andrew Ferrara broad sword belonging to Henry Dundas, Pitt's Secretary of War. But like Addington himself, Lord Hobart seems unaware of how small and child-like he appears, immediately (and repeatedly) taking credit for the victories won by the British navy under Dundas ("Was it not Us?").

In the right foreground, Lord Glenbervie struggles to put on the outsized "Old Slippers" of George Canning, Pitt's Paymaster General, claiming that they are too narrow. This may be intended as a comment upon Canning's frugality. Certain it is that, as the British Museum commentary notes, Canning was reluctant to leave his "present-pay Free Quarters" in London that Glenbervie was now inheriting.

Behind Glenbervie, the two new Treasury secretaries (John Hiley Addington, brother of the Minister, wearing spectacles, and Nicholas Vansittart) are dwarfed by the huge quills of their profession and by the ink stands (serving as hats) of their predecessors, George Rose and Charles Long. The remaining figures are all identified in the British Museum commentary on this print. To their right, "partly hidden by Eldon and Addington, are two unidentified figures: a man wearing a large naval cocked hat, and a lawyer in back view. The former must be St. Vincent who succeeded Spencer at the Admiralty. The latter may be Law who became Attorney General. Between and behind Addington and Hawkesbury is a sulky-looking man in a military coat and an enormous busby in which is a huge pen: 'Wyndham's Cap & Feather'. He is Charles Yorke who succeeded Windham as Secretary of War."

Sources and Reading

- Commentary from the British Museum on Lilliputian-Substitutes, Equiping for Public Service.

- Christiane Banerji and Diana Donald, Gillray Observed, 1999, Ch. 10

- Draper Hill, Mr. Gillray The Caricaturist, 1965, pp.104-5. Pl. 90.

- Draper Hill, The Satirical Etchings of James Gillray, 1976, #72.

- Robin Reilly, William Pitt the Younger, New York, 1979.

- "Addington ministry," Wikipedia

- "First Pitt ministry," Wikipedia

- "Sylvester Douglas, 1st Baron Glenbervie," Wikipedia

- "John Jervis, 1st Earl of St Vincent," Wikipedia

- "Charles Philip Yorke," Wikipedia

- "Treaty of Amiens," Wikipedia

- "Andrew Ferrara," Wikipedia

- Songs in the comic opera of Tom Thumb the Great

- Thomas Wright and R.H. Evans, Historical and Descriptive Account of the Caricatures of James Gillray #260

- Thomas Wright and Joseph Grego, The Works of James Gillray, the Caricaturist; With the History of His Life and Times pp. 276-7.

Comments & Corrections

NOTE: Comments and/or corrections are always appreciated. To make that easier, I have included a form below that you can use. I promise never to share any of the info provided without your express permission.