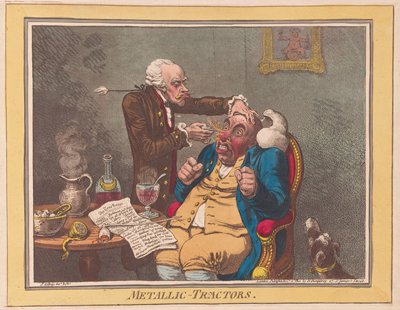

Metallic-Tractors

Metalic-Tractors is a brilliant and memorable portrayal of the medical quackery of two Americans, Elisha and Benjamin Perkins, whose "metallic tractors" were heavily advertised from 1798 to 1802 in London newspapers such as The True Briton, The Morning Post, The London Times, and many others as a cure for a whole host of afflictions in humans and animals.

© Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

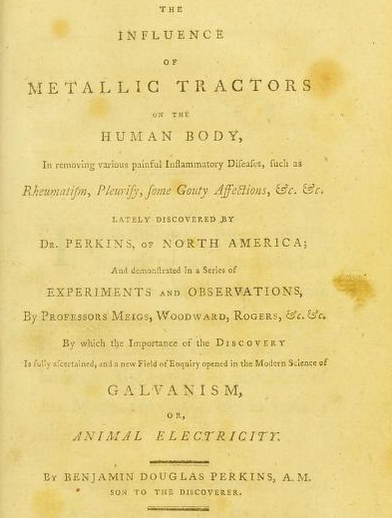

As quoted by William Snow Miller in the Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, Perkins claimed to have discovered

that by drawing over the parts affected in particular directions certain instruments which he formed from metallic substances into certain shapes, he could remove rheumatism, gouty affections, pleurisies, inflammations in the eyes, erysipelas, and tetters; violent spasmodic convulsions, as epileptic fits; the lockjaw; the pain and swelling attending contusions; inflammatory tumours; the violent pains occasioned by a recent sprain; the painful effects of a burn or scald; pain in the head, teeth, ears, breast, side, back and limbs; and indeed most kinds of painful topical affections.

© Phisick: Medical Antiques

Like so many caricatures, the humor of Metalic-Tractors depends upon a stark contrast, in this case of bodily shapes in the fat, round patient, and the thin straight physician, and of demeanors in the exaggerated wide-eyed, teeth-gritting, fist-clenching reaction of the patient versus the cool, calm, professional concentration of the quack doctor in spite of the fiery result of his treatment.

Both figures are surrounded by objects that provide a satiric commentary on their situation. The decanter of brandy, the jug and glass of steaming punch, the accompanying lemon and sugar, the picture of the young bacchus astride a barrel—all suggest that the patient's symptoms of ruddy complexion and bulbous nose have been self-created by his over-indulgence in the pleasures of alcoholic consumption. Meanwhile, the stories featured in The True Briton (on the table) surrounding the central advertisement of the Perkins metallic tractors suggest that the invention belongs in the same class as hoaxes like "the Grand Secret of the Philosopher's Stone with the True way of turning all Metals into Gold" Indeed, Gillray correctly sees this phenomenon as a kind of "Theatre | Dead Alive." And the notice "just arrived from America: the Rod of Aesculapius" slyly compares these metallic rods from America with the mythical rod of the Greek God of medicine.

It's hard to know whether Elisha Perkins was simply a charlatan or whether his success with credulous patients made him an unwitting gull of his own methods. But there is no doubt that father and son were master marketers. In 1795 Elisha sent his son Benjamin to England to promote the device and in 1796 took out a US patent. A former bookseller, Benjamin created a series of pamphlets and advertisements which Gillray would certainly have seen, extolling the efficy of the metallic tractors and citing numerous supporters. He even established a Perkinsian Institute for the poor where the tractors were extensively used.

© Internet Archive

From the start, there were doubters, who saw the tractors as an elaborate scam. One of those, John Haygarth published a pamphlet, On the Imagination as a Cause & as a Cure of Disorders of the Body which conclusively demonstrated that the fake tractors he used on some patients were just as effective as Perkins' expensive tractors used on others, thereby documenting one of the earliest examples of what would later be called the placebo effect. But Haygarth's pamphlet simply prompted further pamplets and rebuttals from Perkins, keeping the name and the device in the public consciousness. Indeeed, Perkins seems to have early appreciated that, as P.T. Barnum is supposed to have said, "There's no such thing as bad publicity." For as Draper Hill documents, there is solid evidence that although Gillray was responsible for the design of the print, and the print itself highly critical of the device, the production was, in fact, commissioned by Perkins.

Sources and Reading

- Commentary from the British Museum on Metallic-Tractors.

- Draper Hill, Mr. Gillray The Caricaturist, 1965, p. 140, Pl. 137.

- Christiane Banerji and Diana Donald, Gillray Observed, 1999, Ch. 13

- "Elisha Perkins," Wikipedia

- Elisha Perkins and his Metallic Tractors, Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine

- "John Haygarth; Wikipedia

- "Galvanism; Wikipedia

- Thomas Wright and R.H. Evans, Historical and Descriptive Account of the Caricatures of James Gillray #506

- Thomas Wright and Joseph Grego, The Works of James Gillray, the Caricaturist; With the History of His Life and Times p. 281.

Comments & Corrections

NOTE: Comments and/or corrections are always appreciated. To make that easier, I have included a form below that you can use. I promise never to share any of the info provided without your express permission.