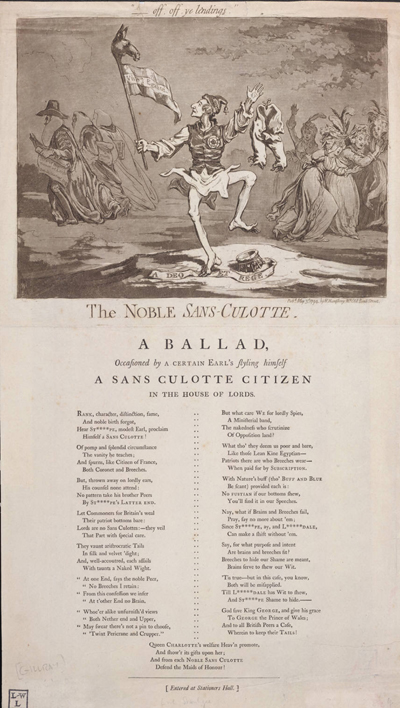

The Noble Sans-Culotte

Gillray's The Noble Sans-Culotte was printed as part of a broadside with "A Ballad Occasioned by a certain Earl's styling himself A Sans Culotte Citizen." It features the radical Whig Earl Stanhope as a combination of fool and madman tearing off his breeches much to the displeasure of his fellow peers and the embarassment of his wife and daughters.

© Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University

Like a fool, he wears a cap and bell and carries a marotte appropriately topped with an ass's head. But the cap is also a revolutionary bonnet rouge and the marotte is a staff flying the French tri-color flag inscribed with "Vive l'Egalite." He appears to be dancing wildly (perhaps the Carmagnole) trampling as he does so his Earl's coronet and the motto of the Stanhope family "A Deo et Rege"—from God and King. And, of course, like all good republicans in Gillray's prints, he is sans culotte, literally without breeches.

Above the print there is a quotation from King Lear, "—off, off, ye lendings". It comes from Act Three, Scene Four when, abandoned by his daughters, Lear has gone mad upon the stormy heath. There he comes upon Edgar disguised as the beggar and madman, poor Tom, and in a fit of unaccustomed sympathy, says

Thou wert better in a grave than to answer with thy uncover'd body this extremity of the sky. Is man no more than this? Consider him well. Thou ow'st the worm no silk the beast no hide, the sheep no wool, the cat no perfume. Ha! here's three on's are sophisticated; thou art the thing itself; unaccommodated man is no more but such a poor, bare forked animal as thou art. Off, off, you lendings! Come unbutton here.

The full context of the quotation poses a question that arises frequently in considering the meaning of Gillray's prints. How much of the allusion should we consider? In this case, are we to assume that Gillray's point is simply that Stanhope is a madman as well as a fool? Or does the suggested equivalence of Lear and Stanhope include a slight, complicating, ray of sympathy for the mad earl in his attempt to identify with the weak and powerless? Appropriately enough, Stanhope had a contentious relationship with his daughters which, according to his granddaughter, later caused him to compare himself to Lear.

The print and broadside were prompted by series of debates in the House of Lords in which Stanhope was a major speaker, It began on March 25th when Stanhope strenuously objected to an assertion by Lord Mansfield made the previous week,

"that if it were possible to engage any considerable number of Frenchmen to excite an insurrection, or rebellion in France against the National Convention, that no possible expence which it could cost this country ought to be spared, and that it was a measure which should be adopted by the British government."

Stanhope was appalled. "It struck him," he said "as an observation. . . abhorrent to all true policy, to genuine religion, and even common humanity."

As a result, on April 4th, Stanhope put forward a motion "to prohibit His Majesty's Ministers and all others from interfering with the internal affairs of France, either by bribing them to insurrections, or dictating as to their form of government." Unfortunately, his arguments for his position included incendiary reflections, based on the Biblical Book of Samuel, upon evils of kingship (which, he said should not be forced upon the French who had already rejected it) and religion (which, he noted, was often "pressed into the service of war and compelled to bear the bloody standard of ambition.")

In response, William Wyndham Grenville, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, confessed that he had "never heard any speech with such indignation" and was sorry to see the Earl's "passions get the better of his reason." He predicted that Stanhope would see "the entire House against him, and the people throughout the country condemn his resolution." As indicated in Gillray's print, the Lord Chancellor (Loughborough), in hat, wig, and robes, as the Speaker of the Lords, agreed with Grenville, and when the resolution was put to the vote, the only dissenting vote was Stanhope's.

Sources and Reading

- Commentary from the British Museum on The Noble Sans-Culotte

- "Charles Stanhope, 3rd Earl Stanhope," Wikipedia

- The Life of Charles, Third Earl Stanhope By Ghita Stanhope, George Peabody Gooch

Comments & Corrections

NOTE: Comments and/or corrections are always appreciated. To make that easier, I have included a form below that you can use. I promise never to share any of the info provided without your express permission.