Operatical Reform, or la Dance a l'Eveque

On March 2, 1798, during a debate in the House of Lords on a Divorce Bill, the Bishop of Durham traced the growing number of petitions for divorce to the baneful influence of French morality (or the lack thereof), and especially French ballet dancers.

The French rulers, while they despaired of making any impression on us by the force of arms, attempted a more subtle and alarming warfare, by endeavoring to enforce the influence of their example, in order to taint and undermine the morals of our ingenuous youth. They sent amongst us a number of female dancers, who, by the allurements of the most indecent attitudes, and most wanton theatrical exhibitions, succeeded but too effectually in loosening and corrupting the moral feelings of the people; and indeed if common report might be relied on, the indecency of those appearances far outshamed anything of a smiliar nature that had ever been exhibited.

In conclusion, the good Bishop proposed a remedy: that "his majesty would be graciously pleased to prohibit the exhibition of those indecent spectacles, and to order those who performed them to be sent out of the country."

The effect was almost immediate. Fearing, no doubt, more drastic measures, the managers of the public theatres began making some proactive changes of their own. On March 5, just a few days after the Bishop's speech, the Morning Chronicle reported that the date of the performance of the new opera of Cinna had been "changed to give time for new dressses, and the dance of Saturday-night was drest with such regard to delicacy as to combine the most rigid decorum with the most graceful elegance." On March 10, the True Briton noted a further improvement.

Mr. TAYLOR, the Manager of the Opera House, has the merit of having led the way in the Reform of Morals at our Theatres. His exclusion of Ladies of a certain description, from the Pit of the Opera, has produced a very pleasing change in the general appearance of that gay parterre.

Over the next several weeks, journalists had a field day with both the prelate's remarks and the managers' reaction to them. Some supported the reforms as necessary to preserve the moral health and well-being of British youth (or at least the country's bishops). Others derided it as a paranoid response to a problem that didn't exist. Gillray's Operatical Reform was one of the first caricatures on the subject and, not suprisingly, it is distinctly ambiguous.

© Trustees of the British Museum

The print purports to show the results of the recent operatical reforms ("a l'Eveque") upon the venue and performers. The two most obvious results are a pit where neither musicians nor audience is to be found; and, second, a token addition of aprons to the performers' diaphanous dresses.

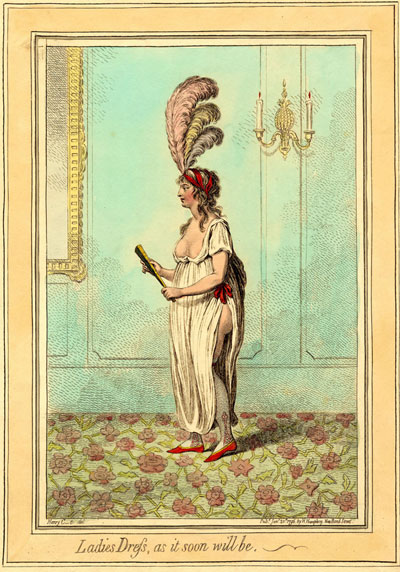

Before going further with an anaysis of Gillray's likely meaning with these changes, it is worth reminding ourselves of the contemporary context. The fashion of low cut, clinging, diaphanous dresses was not new to the ballet in 1798. Indeed it was not even new to fashionable English ladies. Gillray had himself satirized the trend of exposing the female form in several caricatures dating from early 1796, including Ladies Dress, As It Soon Will Be (01/20/1796), The Fashionable Mamma, or the Convenience of Modern Dress (02/13?/1796), and Lady Godina's Rout, or Peeping Tom Spying Out Pope Joan (03/12/1796).

© Trustees of the British Museum

Neither was the erotic attraction of ballet performers. The images of prelates and government officials "inspecting" opera performers in 1798 as seen in Woodward's print, A m(eye)nute regulation of the opera step- or an episcopal examination (March 9, 1798), had obvious predecessors like the 1796 Richard Newton print, Mademoiselle Parisot.

Madamoiselle Parisot

[Erased, 1796]

© Trustees of the British Museum

What WAS new since 1796 was a greatly heightened sense of the threat of French revolutionary thinking in England and the linkage of that revolutionary thinking to the ballet. Two attempted invasions of Britain had occurred. A plot to aid the French by representatives of the United Irishmen had been discovered. There had been dangerous mutinies of British sailors at Nore and Spithead. Long-time rights of British citizens such as habeas corpus were about to be suspended (again). And even as the newpspapers were reporting the Bishop's reflections on revolutionary immorality, the principal violinist and leader of the orchestra at the King's Theatre, Giovanni Battista Viotti, was being deported for suspected French sympathies.

The violin crowned with a bonnet rouge in Gillray's print, then, is a reference to the departure of Viotti and the potential loss of the entire opera orchestra as a result. The absence of any other audience in the pit may allude to the recent ban of ladies of a certain description that was now being enforced.

On the stage, framed by an amused satyr on one side and a clothed but possibly interested Medici Venus on the other, three dancers can be identified. From right to left, they are: Rose Didelot, the subject of an earlier Gillray print 'No flower that blows, is like this rose', the young Celine(?) Parisot who had become famous for raising a leg to a new and precisely horizontal position, and (most likely) Marie-Louise Hilligsberg, a long-time fixture of the ballet company of the King's Theatre. In compliance with the "new fangled orthodox rules," they are wearing aprons that cover their pudenda, but maintain the diaphanous drapery that covers yet reveals their breasts and bottom. Gillray's choice to portray the three women dancing together is intended (I believe) to parody paintings and sculptures of the three graces where at least one of the graces is often facing away from the viewer, and where diaphanous drapery or outright nudity is considered high art.

The Three Graces: Detail from Primavera (1485-87)

© Wikimedia Commons

The satyr on the left of Gillray's print seems to be well aware of the erotic potential of the dance on the stage, and the mask with its phallic nose covering his genitals is a kind of analogue to the implementation of the bishop's measures which so far pretends to hide but still suggests what lies beneath. He puts his finger up to his lips as if to ask the audience for their silent complicity. And he certainly received it. This was no moral turning point in either opera or ballet. Indeed over the next year, the generally more restrained performances of Mme Didelot lost ground to the edgier, more erotic attitudes of Mlle Parisot who now began to appear as a prima ballerina.

Sources and Reading

- Commentary from the British Museum on Operatical Reform, or la Dance a l'Eveque.

- Mademoiselle Parisot, Wikipedia

- Madame Rose Parisot, 'Attitudinarian,' Vintage Pointe

- Madame Hilligsberg, Art Gallery NSW

- "Giovanni Battista Viotti," Wikipedia

- Shute Barrington, Wikipedia

- Thomas Wright and R.H. Evans, Historical and Descriptive Account of the Caricatures of James Gillray #448.

- Thomas Wright and Joseph Grego, The Works of James Gillray, the Caricaturist; With the History of His Life and Times, p. 253-254.

Comments & Corrections

NOTE: Comments and/or corrections are always appreciated. To make that easier, I have included a form below that you can use. I promise never to share any of the info provided without your express permission.