Pantagruel's Victorious Return to the Court of Gargantua

The Life of Gargantua and of Pantagruel is a series of five French novels by François Rabelais about two giants, Gargantua and his son Pantagruel. In the first book, Pantagruel returns from the University to fight against the Dipsodes to preserve the lands of his father. Written in an extravagant style that in Gillray's time was often compared to Laurence Sterne's in Tristram Shandy, Rabelais' novels might have seemed to Gillray like a verbal erquivalent of his own often extravagant caricature.

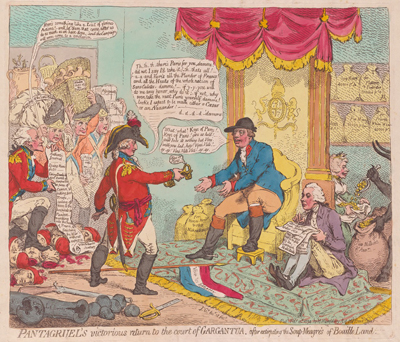

The impetus for this print was the brief return of King George's favorite son, Prince Frederick, the Duke of York, from Flanders where he had been leading a British/Hanoverian army against France as part of a larger Coalition including Austria, Prussia, and the Dutch Republic. But it is not only the stumbling drunk Prince being attacked in this print. The King, the Prime Minister, and the Queen all come in for their fair share of Gillray's satire, most of it resurrecting earlier and familiar lines of attack.

© Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

In Fatigues of the Campaign in Flanders (May 20, 1793), Gillray had portrayed the 29 year old Duke as spoiled and drunken, (mis)using his troops as servants, his artillery as benches, and celebrating all out of proportion to his accomplishments. Here, the drunken Prince, with a now empty bottle in his pocket, boasts that he has brought with him "all the Plunder of France" but which turns out to be "Breeches of the Sans Culottes," (who don't wear, or need, breeches) "Wooden Shoes of the Poissards," (i.e.the clogs of fisherwomen, not exactly of great value to English troops), bales of "Assignats" (the famously worthless French currency), and stray pieces of damaged swords and artillery.

Meanwhile his appropriately named Secretary "Js Suckfizzle" unfurls a list of patently false accomplishments, featuring "Taking Dunkirk" and concluding with "finishing the War without Expence." In fact, Dunkirk was NOT taken. A delay in the delivery of provisions forced the Prince to postpone the attack, eliminating the advantage of surprise and allowing the French to call up 30,000 more reinforcements and to flood the southern marshes around Dunkirk. So when the Duke and his approximately 15,000 troops finally attacked, they were now forced to fight on unfavorable ground against a French army three times their size. Suffering approximately 10,000 casualties acccording to Robert Harvey, they made a quick and ignominious retreat. And as for expenses, since Britain could not quickly field an army from among their own citizens, they relied on paying other countries to do their fighting—£1 million for Prussia's 62,000 men alone.

The only person who seems to believe the Prince's drunken assertions and self-comparisons with the greatest classical generals is his goggle-eyed Father, George III who accepts the supposed "Keys of Paris" while recalling Julius Caesar's more accurate summation of his own war against the French: veni, vidi, vici (I came, I saw, I conquered). But in fact it was the British decision to attack Dunkirk (against the advice of Austria) that virtually ensured Paris would NOT be taken and the war would go on indefinitely.

Gillray had already portrayed the Royal Family's gullibility and greed in The Introduction, another print involving the favored Duke of York in which the rumored (and exaggerated) dowry of York's fiancée is met by his parents with decidedly un-royal enthusiasm.

© Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University

In Pantagruel the King and Queen are again portrayed as greedy and grasping. At the feet of the King (significantly wearing a jockey/hunting cap) we can see money bags labeled "for Hors[es], Hounds, & other Nicknackatories." Meanwhile the Queen holds out an apron being filled with money from a devil while behind her she maintains shelves of money bags categorized according to the Queen's "needs": "Spy Money 40000 pr A"; "for Flatterers & Toad-eaters 10000 pr A"; 10000; "Pin Money 50000 p Ann"; "for Private Whim Wham[s] 50000 pr [A]"

Funding these expenses is the ever-inventive Pitt's job (sitting on the floor next to the king) by obtaining loans totaling £11 million and levying taxes on more and more items, including "Bricks" and "Brandy" but likely (in Gillray's view) to include "Water" and "Air" before too long.

Sources and Reading

- Commentary from the British Museum on Pantagruel's Victorious Return to the Court of Gargantua.

- "Gargantua and Pantagruel," Wikipedia

- "Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany," Wikipedia

- "Flanders campaign," Wikipedia

- "War of the First Coalition," Wikipedia

- Tobert Harvey, The War of Wars, London 2006, especially the chapters "Dunkirk" and "The Grand Old Duke of York."

- Thomas Wright and R.H. Evans, Historical and Descriptive Account of the Caricatures of James Gillray #110.

- Thomas Wright and Joseph Grego, The Works of James Gillray, the Caricaturist; With the History of His Life and Times, p. 176.

Comments & Corrections

NOTE: Comments and/or corrections are always appreciated. To make that easier, I have included a form below that you can use. I promise never to share any of the info provided without your express permission.