Introduction to the Elements of Skateing

Ice Skating in Britain

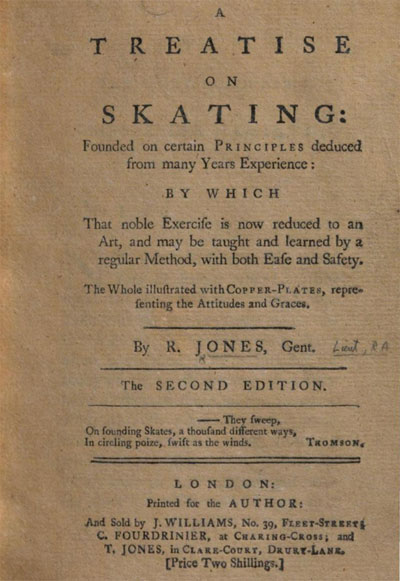

According to A Treatise on Skating, first published in 1772 and reprinted and/or expanded in 1775, 1780, and 1797, ice skating in Britain was known and practiced as early as the reign of Henry II. At that time a monk by the name of Fitzstephen wrote that when the moor at the North Wall of Moorfields is frozen

great companies of young men go to sport upon the ice, and bind to their shoes bones, as the legs of some beasts. . . and these men go on with speed, as doth a bird in the air, or darts shot from some warlilke engine.

© Google Books

Not suprisingly, skating generally caught on first and most thoroughly in the colder, northern parts of Britain. The first record of skating on metal skates dates from around 1660 with the return of the Scottish King Charles II who had spent a good part of his exile in the Netherlands. And the first organized club devoted to the sport was the Edinburgh Skating Club established, according to most commentators, in the 1740s.

As Robert Jones points out in his Treatise on Skating, however, ice skates and ice skating developed very differently in Britain than they did in the Netherlands.

Skating among the Dutch is not so much an exercise or diversion, as business and necessity; the nature of their country and the continuance of their frosts make it so; consequently safety and expedition is all they have to consider; and I have before shewn that this is sufficiently attended to in the formation of their skates. In England, the case is different; skating is used here as an exercise and diversion only; hence an easy movement and graceful attitude are the sole objects of our attention. To arrive at these, nothing can be better imagined than the present form of our skates.

The Portrayal of Skating Before Gillray

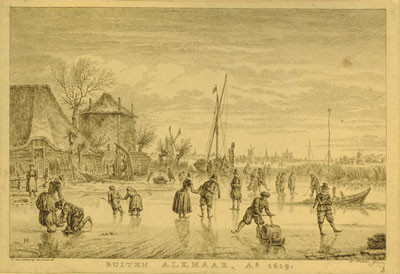

Largely because of this difference in weather, most of the images of skating before 1800 derive from Dutch artists or foreign artists depicting Dutch or Flemish winterscapes. Examples include Skating before the Saint George's Gate, Antwerp (1565) by Frans Huys after Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Vue de Santvliet village de Hollande (1748) by Jacques Philippe Le Bas after Aert van der Neer, and (below) Buiten Alkmaar, Ao 1619 by Simon Fokke after the prolific artist of skaters Hendrick Avercamp.

Buiten Alkmaar, Ao 1619

[1725 - 1784]

© Trustees of the British Museum

As in the many drawings, paintings, and prints by Hendrick Avercamp, the skaters in these works (and there are always many) are most often seen from a distance. And though, when looked at closely, some of Averkamp's paintings contain mishaps similar to those we see later in Gillray, the skaters are clearly part of a much larger winterscape which seems designed to assure the viewer that work and play in Holland go on as usual whether there is ice or not.

The earliest English prints and drawings devoted to ice skating begin to appear after the publication of Robert Jones's Treatise on Skating in 1772 and may have been prompted by the popularity of the book and several unusually cold winters throughout England in the 1780s and 90s. Rowlandson, for instance, created several drawings with skaters, now in the British Museum, (probably in the 1780s) including Skating on the Serpentine in Hyde Park, and A Scene on the Ice. Like so many of Rowlandson's works, they portray the triumph of nature, chaos, and accident over human intent and design. Skaters lose their balance, fall on top of one another, and expose themselves in awkward and suggestive positions while one skateless figure on the extreme left enjoys the scene. But though the drawings clearly belong to comic caricature as opposed to the more realistic reportage of Avercamp's genre scenes, these drawings still show the influence of their Dutch predecessors in the size and number of figures and the space devoted to the background. But neither of these drawings appear to have resulted in published prints.

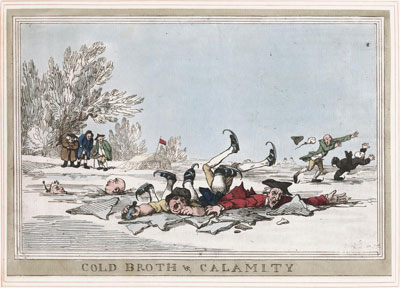

The only skating scene by Rowlandson that Gillray would almost certainly have seen is Cold Broth & Calamity published in 1792 which shows skaters who have fallen through the ice. In its caricatured expressions and its focus on a small number of foreground figures supplemented by a few background figures, it anticipates Gillray's Elements of Skateing. But Gillray, as usual, goes his own way. He is the only one to create a multi-print series devoted to skating, and when he depicts a skater fallen through the ice in one of his prints, he focuses on the struggle between the fallen skater and his "Passing Friend."

Cold Broth & Calamity

[1792]

© Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University

Elements of Skateing

Gillray's Elements of Skateing consists of four plates, each one of which can stand alone. So for simplicity's sake I treat them by subtitle in alphabetical order:

- Attitude! Attitude is Every Thing!

- The Consequences of Going Before the Wind

- A Fundamenal Error in the Art of Skaiting

- Making the Most of a Passing Friend. . .

Each plate consists of two central skaters. And in stark contrast to most of Rowlandson's skating works, the paucity of figures and the background trees suggest a rural rather than a London setting like Hyde Park and the Sepentine. That fact may lend some support to the theory that the series is based on either sketches or ideas by Gillray's friend the Revered John Sneyd, Rector of Elford in Staffordshire. But overall the treatment is so incisive, the interaction of the figures is so well done that I'm still inclined to attribute the design and production wholly to Gillray.

But they can be seen as a kind of evolution from Gillray's earlier four-part series on hounds and fox hunting based on designs by Brownlow North (see Hounds Finding (1800). Both series focus on a small number of figures. Both portray the dangers of a sport. Both attempt to find some degree of humour in what would ordinarily be painful (even deadly) situations. But in the Elements of Skateing, there are fewer distractions from the central event and a progressive darkening from the first mostly comic print to the last two mostly grotesque prints where the cruelty of the depiction makes one distinctly uncomfortable.

Sources and Reading

- Commentary from the British Museum on Elements of Skateing: Introduction.

- Rachel Knowles, "Ice Skating in Regency London," Regency History

- "Ice skating," Wikipedia

- "Ice Skating," Encyclopedia Britannica

- Robert Jones, A Treatise on Skating

- "Robert Jones (artilleryman)," Wikipedia

- "The History of British Winters," netweather.tv

- Thomas Wright and R.H. Evans, Historical and Descriptive Account of the Caricatures of James Gillray #540.

- Thomas Wright and Joseph Grego, The Works of James Gillray, the Caricaturist; With the History of His Life and Times, p. 326.

Comments & Corrections

NOTE: Comments and/or corrections are always appreciated. To make that easier, I have included a form below that you can use. I promise never to share any of the info provided without your express permission.