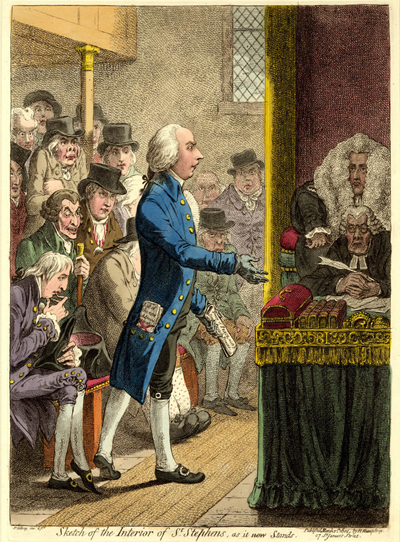

Sketch of the Interior of St Stephens, as it Now Stands

As the title suggests, this is a view of the interior of St. Stephens at a specific moment in time, March 1st 1802, with the new Prime Minister Henry Addington addressing the chamber.

© Trustees of the British Museum

Part of the Palace of Westminster, St. Stephen's (Chapel) was from 1548 until it burned down in a fire in 1834 the debating chamber for the House of Commons. The altar was replaced with a raised platform where the Speaker of the House sat in the Speaker's Chair. Before him were two scribes and a table with the ceremonial mace, symbol of power. The choir stalls on either side of the altar then became the ministerial and opposition benches which face one another— the ministerial benches to the right of the speaker; the opposition benches to the left. In this "sketch", Gillray portrays only the ministerial side of the House. It was on this side where the most changes were taking place.

The most important of these changes was the resignation of William Pitt as Prime Minister in February 1801 (over the issue of Catholic Emancipation) and his replacement with Henry Addington in March. Pitt had been Prime Minister since 1783, and his resignation was unexpected to put it mildly. Addington was considered a somewhat suprising choice as successor because he lacked Pitt's deep knowledge of finance and his nearly unparalleled powers of persuasion. Indeed there was suspicion that Addington's weakness was intentional so that he would become an easier pawn for Pitt. As the Anti-Jacobin Review and Magazine Vol 24 put it,

it was generally believed, from his intimate connexion with Mr. Pitt, from his apparent unfitness for the situation, and from Mr. Pitt's reputed love of power, that Mr. Addington was only a glove for the hand that still continued to guide the reins of government.

This last metaphor may, in fact, suggest why the new Prime Minister is portrayed wearing gloves. Since 1789, Addington had been Speaker of the House and by law forbidden to take an active position in debate. His position was now taken by the diminutive Charles Abbott whose face is being swallowed up by his enormous Speaker's wig.

Since a number of Pitt's ministry had joined their Prime Minister in resigning from office, one of Addington's first responsibilities was to fill new cabinet positions. In Addington's pocket, then, we see a paper protruding labeled "List of the New Administration."

But the most pressing need was the one alluded to in the other papers held in Addington's left hand: the "Treaty of Peace with ye Democratick Powers." i.e. France. After the departure of the most pro-war Tories, William Windham and Henry Dundas who had resigned with Pitt, the newly appointed Foregn Secretary, Robert Jenkinson (aka Lord Hawkesbury, seated right behind Addington with his finger to his lips) had pursued a much more conciliatory policy with France. At the time of this print, in fact, the preliminaries of the eventual Treaty of Amiens had already been signed, and the final treaty (signed March 25, 1802) was under debate. The Whigs had argued for peace with France for years, so we now see two of them, John Nicholls and George Tierney, sitting in the second row behind Addington.

Gillray's view of all this is distinctly ambiguous. The description of the treaty as one made with the "Democratick Powers" suggests perhaps a deal with the devil. In Gillray's vocabulary,"democratic" is usually associated with leveling, sans culottes, and revolutionary excess. Think of his famous portrait of Fox in A Democrat, or Reason & Philosophy. But Addington himself is perhaps the least caricatured figure in the print. And like Pitt in Integrity Retiring from Office he is shown in the pose of a classical statesman. My sense is that like most of England, Gillray was taking a "wait and see" attitude. The country was tired of war, and tired of the increased taxes that were required to support it. If Buonaparte were also tired of war and ready to be more of a Consul and less of a general, maybe Addington's policy was the best after all.

By contrast, in the 1804 print, Britannia between Death and the Doctor's, however, Gillray was no longer reserving judgment. By then it was clear that Addington's prescriptions (he was a doctor's son) had only left Britain in a weakened and vulnerable state. Now fully caricatured, Addington is shown being unceremoniously booted out the door by a resurgent Pitt.

© Trustees of the British Museum

Sources and Reading

- Commentary from the British Museum on Sketch of the Interior of St Stephens, as it Now Stands.

- "Addington ministry," Wikipedia

- "Charles Abbot, 1st Baron Colchester," Wikipedia

- "Henry Addington, 1st Viscount Sidmouth," Wikipedia

- "Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool," Wikipedia

- "John Nicholls (MP)," Wikipedia

- "George Tierney," Wikipedia

- "William Wilberforce," Wikipedia

- "Treaty of Amiens," Wikipedia

- Thomas Wright and R.H. Evans, Historical and Descriptive Account of the Caricatures of James Gillray #265.

- Thomas Wright and Joseph Grego, The Works of James Gillray, the Caricaturist; With the History of His Life and Times, p. 284.

Comments & Corrections

NOTE: Comments and/or corrections are always appreciated. To make that easier, I have included a form below that you can use. I promise never to share any of the info provided without your express permission.