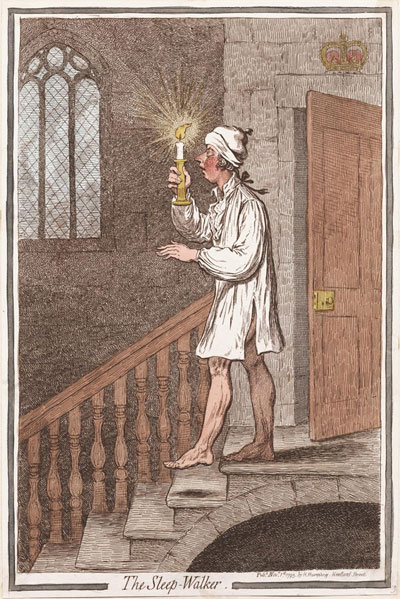

The Sleep-Walker

Gillray was arguably the most innovative English portrait caricaturist of the 18th and 19th centuries. Starting with profile busts and full-length profiles in the 1780s, Gillray later played countless variations on this oldest and most revered of traditions in caricature.

© Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University

Sometimes he portrayed his subjects seated or on horseback instead of standing. Sometimes he changed the profile perspective for a three quarter, full face, or even a rear view. Sometimes he added varying degrees of background to identify or satirize his subject. And sometimes he grafted a caricatured head to the body of some other object like a mushroom or butterfly.

The Sleep-Walker can be seen, then, as another experiment—successful, even masterful, in some ways, and not so successful in others. Here he shows Prime Minister William Pitt in full-length profile with a simple title that in most portrait caricatures would provide a clue to the identity of the subject. But instead of placing Pitt against a neutral background, Gillray puts him in a highly specific and unusual position—at the top of a dark stair case outside the door to the King's bed chamber, guided only by the taper in his hand, with his foot poised to take a treacherous step down. Portraying Pitt dressed only in his night shirt, with his eyes closed, Gillray does not use the title of his print The Sleep-Walker to identify Pitt. By 1795 Gillray could safely assume that everyone would recognize Pitt's distinctive profile, especially in Gillray's version. Instead, the image and title are there to characterize or brand Pitt, portraying him as an imminent threat to himself, his King, and implicitly to the country.

Under Pitt's leadership, 1795 had been an awful year for England. In January, the English attempt to hold on to Holland failed miserably, forcing the King's blood relation, William V, Prince of Orange, to flee his country and watch from Hampton Court as the French took over the Low Countries and established the pro-French Batavian Republic. In March there were a series of food riots throughout the country owing to bad harvests. In April, Prussia, one of Britain's First Coalition partners against France, signed a separate peace agreement with the revolutionaries, ceding the left bank of the Rhine to the French. In June, the attempt to support Royalist rebels in retaking the Vendee also failed with a decisive loss at Quiberon bay. And in July, another Coalition partner, Spain, made its own separate peace with France, leaving Britain with mounting debts and a dwindlng number of allies.

Gillray's highly critical view of a prime minister sleep-walking through his job would not have come as a complete surprise. Earlier in the year in God Save the King in a Bumper (May 27, 1795) Gillray had portrayed Pitt and Dundas as a pair of drunkards celebrating not the King but their own hold on power. In June in Blindmans Buff, or Too Many for John Bull, Pitt is shown blithely stealing money from John Bull's coat while John Bull himself staggers around blindly, attacked on all sides by false friends and enemies. And in the same month, Gillray portrayed Pitt's Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, the man who represented Pitt's vision of the war against France as near-sighted and self-serving in two ironically titled prints: A Keen-Sighted Politician Finding out the British Conquests and A Keen-Sighted Politician Warming His Imagination. Finally, on the same day as The Sleep-Walker, Gillray also published The Republican Attack which shows Pitt as coachman of the King's carriage driving over the prostrate form of Britannia.

Because of these other, more specific prints, Gillray may have thought of The Sleep-Walker as a kind of capsule summary of Pitt's performance. It is brilliantly succinct, containing only three words in the entire print space (only two if you count Sleep-Walker as one word). Unlike most satiric prints with speech bubbles, notes protruding from pockets, or relevant pictures on the wall, it has only one small detail (the King's crown) that may be said to convey information. But the central image of the sleep-walker is all the more powerful (and memorable) for its radical simplicity.

Sources and Reading

- Commentary from the British Museum on The Sleep-Walker.

- Draper Hill, Mr. Gillray The Caricaturist, 1965, p. 58

- "William Pitt the Younger," Wikipedia

- "War of the First Coalition," Wikipedia

- Thomas Wright and R.H. Evans, Historical and Descriptive Account of the Caricatures of James Gillray #131.

- Thomas Wright and Joseph Grego, The Works of James Gillray, the Caricaturist; With the History of His Life and Times, p. 191.

Comments & Corrections

NOTE: Comments and/or corrections are always appreciated. To make that easier, I have included a form below that you can use. I promise never to share any of the info provided without your express permission.