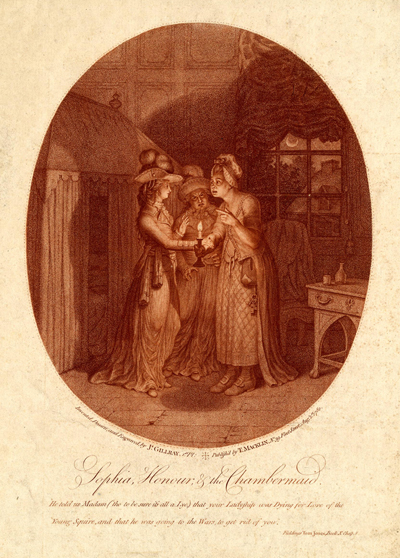

Sophia, Honour, & the Chambermaid

This is the first of a paired set of carefully crafted stipple engravings in the manner of Francesco Bartolozzi illustrating two scenes from Henry Fielding's classic novel Tom Jones. The other print is Tom Jones, Partridge, & the Beggar. Both were published in 1780. Taken together, they represent the first of several attempts Gillray made during the 1780s to break away from satiric print-making and to produce works that would gain him the reputation of a "serious" artist rather than that of a caricaturist. And they were clearly prompted by his recent training and experience at the Royal Academy Schools.

© Trustees of the British Museum

In April 1778, after he had already been working as an etcher and engraver for Harry Ashby creating buttons and business cards, and sporadically producing political and social satire for William Humphrey, Matthew and Mary Darly, and other print-sellers, Gillray was admitted to the prestigious Royal Academy Schools. It must have represented to him a clear recognition of his talent and potential as an artist. We don't know exactly what course of study he pursued, but it likely included anatomy and figure drawing from the life.

Perhaps as important as the courses, however, were opportunities to meet artists and engravers like Philip de Louthbourg, John Hamilton Mortimer, Francesco Bartolozzi, and Giovanni Cipriani (who were or became part of the Royal Academy staff), to view and participate in the competitions and exhibitions, and to witness the annual address of the President of the Academy, Sir Joshua Reynolds. Here Gillray would have seen, embodied in these men, a life as a professional artist.

Apart from a career as a portrait painter (which Gillray seems to have at one point entertained), the most lucrative artistic careers in the late 18th century were as an engraver of fine prints based on paintings by Royal Academy members like Angelica Kauffman, Benjamin West, and the great Sir Joshua Reynolds himself, or as an illustrator of scenes based on plays, poems, or novels. The former, of course, required the permission and cooperation of the artist, which could only obtained through inside connections or an established reputation as a preeminent etcher/engraver. Creating an illustration for a published text, on the other hand, required only a copy of the work and a willingness to invest the time and effort. The runaway success of Samuel Richardson's Pamela illustrated by the Frenchman Gravelot, and later by Francis Hayman and Joseph Highmore must have convinced Gillray that illustrating an already popular novel was likely to be a safest path for a young aspiring engraver like himself.

Though later famous for his Poets Gallery (begun in 1787) consisting of illustrations of well-known poems and plays, and for his monumental illustrated Bible (1790-1800), in 1780 Thomas Macklin, the publisher of Gillray's illustrations, had only been in business for a year, so Gillray's aspirations as an artist and Macklin's as a publisher and print-seller must have dovetailed nicely.

There had been at least one attempt to provide illustrations to Henry Fielding's Tom Jones before this, but it had come from the collaboration of foreign-born artists—the Frenchman Gravelot and the Dutch Jan Punt for a French translation of the novel. So far as I've been able to tell, Gillray was the first Englishman to illustrate Fielding's masterpiece.

Plate 1 shows a scene from Book X, Chapter 5. The heroine of the novel, Sophia Western, her maid, Honour Blackmore, and Susan the chambermaid are upstairs in one of the rooms at the Inn at Upton where, coincidentally, Tom, his companion, Partridge, and Mrs. Waters (aka Jenny Jones) are also spending the night. The chambermaid is retailing the kitchen gossip she has heard below stairs from Partridge, which like most gossip is no more than half correct and certainly misleading.

He told us Madam ('tho to be sure it's all a Lye) that your Ladyship was Dying for Love of the Young Squire, and that he was going to the Wars, to get rid of you.

The title and caption are exquisitely engraved in a style that would have made Gillray's first master, Harry Ashby, proud. According to Draper Hill, "Ashby favoured rich curving lines, abandoning the earlier taste for ornamental knots and sprigs." (p. 15)

The room with its patterned wall, wooden floor, curtained bed is carefully delinated, and each of the three figures is distinguished from one another by the clothes she is wearing and the unique expression on her face. Sophia is all elegance with the kind of classical beauty of profile that the 18th century preferred. Her maid, Honour, is shown as proud, disagreeable, and grasping (for money and recognition). Susan, the chambermaid, is portrayed with the rough clothes, patched purse, and work shoes of a lower class servant. Her face reveals her anxiety about talking to a lady as elegant as Sophia, and especially while delivering unwelcome news.

Signed "Invented, Drawn, and Engraved by Js. Gillray," the 24 year old Gillray was clearly and rightfully proud of this effort. Not only has he demonstrated, as Draper Hill remarks, "a considerable facility in the Bartolozzi manner" of stipple engraving (pp.21-22), but he has also taken a page from Wright of Derby's A Blacksmith's Shop (1771) by introducing two sources of light—the light from the candle illuminating the faces of the three women, and the light from the moon seen through the window which illuminates the substantial cottage beyond the Inn. By making the local illumination of the room so much more prominent however, the print not only demonstrates Gillray's proficiency in complex illumination, it reinforces tht subject of the illustration—the half-lights and half-truths of of the moment.

To appreciate Gillray's accomplishment here, it is worth contrasting it with Gravelot's Frontispiece to the illustrated edition of the French translation, which shows the moment where the baby Tom Jones is found in Squire Allworthy's bed upon his return from three months in London. The room is minimally depicted, the faces are unexpressive, and the light from the candle has none of the fidelity to the real effect of candlelight that we see in Gillray's version. The drama of the moment is completely lost.

© Los Angeles County Museum of Art

NEXT PLATE - Tom Jones, Partridge, & the Beggar→

Sources and Reading

- Commentary from the British Museum on Sophia, Honour, & the Chambermaid.

- Draper Hill, Mr. Gillray The Caricaturist, 1965, pp. 15, 21-22.

- Book Illustration in Eighteenth-Century England

- The Royal Academy of Arts and its Anatomical Teachings

- "Thomas Macklin," Wikipedia

Comments & Corrections

NOTE: Comments and/or corrections are always appreciated. To make that easier, I have included a form below that you can use. I promise never to share any of the info provided without your express permission.