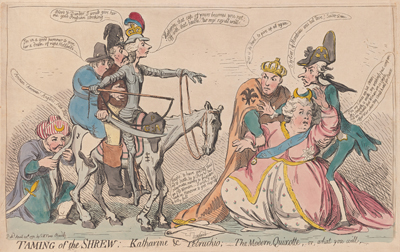

Taming of the Shrew. . .

In the aftermath of the American Revolution, Prime Minister William Pitt tried unsuccessfully to stay clear of European entanglements, pursuing a foreign policy supporting a "balance of power" in Europe which would enable Britain to reduce its national debt and focus on trade. One of the chief perceived obstacles to a favorable balance of power was Catherine the Great of Russia who, in a series of wars with the Turks of the Ottoman Empire, had acquired Crimea, parts of Moldavia and Wallachia and, most importantly, the strategically located port and fortress of Ochakov. She was assisted by the Emperor of Austria, who had been carrying on his own war with the Ottoman Empire since the Austro-Russian Alliance of 1781.

Forming a "Triple Alliance" with Prussia and the United Provinces (Netherlands), against Russia, Pitt hoped to "tame the shrew" Catherine and intimidate her into returning some of the captured lands to the Turks. Prussia hoped to gain additional territories from the alliance, but the United Provinces were a somewhat reluctant participant because of economic ties to Russia.

© Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

In this complex print, then, Gillray tries both to capture the complicated inter-relationships of the countries at the time and to provide his own commentary on them. On the left side of the print, Pitt appears as a Quixote-like knight errant on a tired-looking steed with his two companions of the Triple Alliance shielding the Turkish Sultan. Prussia (with the sword) threatens Catherine with a "good Prussian stroking," but the weaponless United Provinces, holding on to Prussia, and looking more frightened than formidable, offers nothing more threatening than a drink of Holland's gin.

On the right side, Catherine seems genuinely frightened, falling away from the commandingly outstretched arm of Pitt and seemingly giving in to Pitt's demands. Her two supporters, Austria and France offer little more than lamentation. Austria cries "Das is de devil, to give up all again." France, the long-time foe of anything proposed by the English, regrets that Mirabeau (who had died a few weeks before this print) was no longer alive to defend French interests.

Gillray's extended title, Taming of the Shrew; Katharine & Petruchio; The Modern Quixotte, or what you will, provides at least two "frames" for interpreting the print. In the first, Pitt is cast as Petruchio demanding from Catherine complete obedience to his will. And, in fact, the words Pitt speaks derive from Act V Scene 2 of The Taming of the Shrew where Petruchio demonstrates his power over his new wife.

Katherine, that cap of yours becomes you not.

Off with that bauble, throw it underfoot.

In Gillray's version, however, that cap is a Turkish crescent, symbolizing (as the British Museum commentary notes) the lands Catherine has seized from the Ottoman Empire. But instead of ordering her to "throw it underfoot," Pitt (wearing a coronet atop his helmet) assumes the power and hauteur of a king and reinforces his demand that she get rid of "that bauble" by declaring "'tis my royal will,"

Catherine's reply also derives from Act V Scene 2 of The Taming of the Shrew specifically from two of Katherine's speeches when, speaking for wives, she addresses Bianca and the Widow and reproves them for not obeying their husbands. Here is Shakespeare's version:

My mind hath been as big as one of yours,

My heart as great, my reason haply more,

To bandy word for word and frown for frown.

But now I see our lances are but straws,

Our strength as weak, our weakness past compare,

That seeming to be most which we indeed least are. . . .

I am ashamed that women are so simple

To offer war where they should kneel for peace;

Or seek for rule, supremacy and sway

When they are bound to serve, love, and obey.

In Gillray's version, (much to the chagrin of Austria and France) Catherine's words seem like a complete capitulation to Pitt's demand.

I see my Lances are but straws; My strength is weak, my weakness past compare; And am asham'd, that Women are so simple To offer War when they should kneel for Peace.

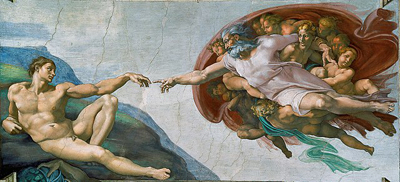

But, of course, this is not the end of it. Gillray provides a second interpretative frame. In that reading, Pitt is not the dominating and successful Petruchio but the hapless and deluded Don Quixote. Part of Pitt's delusion is thinking that he can assume royal power as easily as changing the name on his saddlebag and adding a coronet to his helmet. But the other part is believing that "a Boy & his playmates" can long intimidate the leaders of Russia, Austria, and France. The Triple Alliance as Gillray portrays them are not powerful but pathetic. And the seemingly dominant outstretched arm of Pitt, based on the creation of Adam in the Sistine Chapel, is not that of an omnipotent God, but the all-too-human Adam whose frailty is exposed by a woman.

Between the opponents and centrally located in Gillray's print are two things: the plan of the fortress of Ochakov and even moreso the head of Pitt's pathetic steed. The plan of Ochakov is there, of course, as one of the principal objects of the dispute between the two parties. But the head of Pitt's steed is there, I suspect, because it represents the "horse sense" of Gillray and most Englishmen of the time who would not have seen the value of Pitt's quixotic efforts.

Heigho! to have myself thus rid to death, by a Boy & his playmates, merely to frighten an Old Woman.

In fact, Gillray seems to have been remarkably prescient. Catherine did NOT back down, the Triple Alliance fell apart in July 1791, and the Sultan was forced to sign peace agreements with both Austria and Russia in August 1791 and January 1792 respectively, losing considerable territory in the process. Pitt, for his part, was thoroughly embarrassed by the outcome and almost lost Parliamentary support when an investigation revealed how much he had gambled on the armament against Russia and how little he had gained.

Sources and Reading

- Commentary from the British Museum on Taming of the Shrew. . ..

- Draper Hill, Mr. Gillray The Caricaturist, 1965, p. 38n

- "William Pitt the Younger," Wikipedia

- "Catherine the Great," Wikipedia

- "Triple Alliance (1788)," Wikipedia

- "Russo-Turkish War (1787-1792)," Wikipedia

- Thomas Wright and R.H. Evans, Historical and Descriptive Account of the Caricatures of James Gillray #51

- Thomas Wright and Joseph Grego, The Works of James Gillray, the Caricaturist; With the History of His Life and Times p. 125

Comments & Corrections

NOTE: Comments and/or corrections are always appreciated. To make that easier, I have included a form below that you can use. I promise never to share any of the info provided without your express permission.