The York-Lennox Dispute

On May 26, 1789, there was a duel between the Prince of Wales's brother, Frederick, Duke of York, and Lt. Colonel Charles Lennox, the nephew of the 3rd Duke of Richmond and a member of the Duke's regiment of the Cold Stream Guards. Though, as I argue in Brunswick Triumphant, there were pre-existing political and dynastic reasons for the hostility between the Prince and Lennox, those were never explicitly stated by the two participants. Instead, they were hidden behind a succession of gentlemanly pretexts.

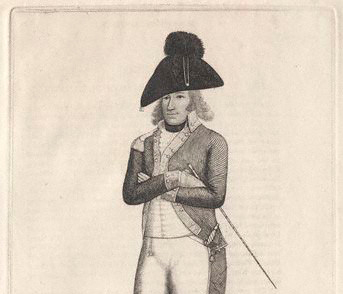

Frederick Augustus, Duke of York

[1788/1789]

© National Trust, Waddesdon Manor

As reported in the newspapers of the time, the Duke of York claimed that in his presence words had been made use of to Colonel Lennox "that no Gentlemen ought to submit to," i.e. that Lennox had been insulted and had not responded. This would seem to have been a matter for Lennox, not the Duke of York, to decide. But Lennox was a member of the Prince's regiment of the Cold Stream Guard, and in discussing the matter before the other soldiers, York and/or Lennox made it, arguably, a matter of regimental honor.

Lennox denied having heard any such words, and asked the Prince to inform him what those words were and who spoke them. The Prince would only say that they were spoken before him at Daubigny's Club but declined to declare what was said or by whom.

Lennox then wrote a letter to the members of Daubigny's

desiring each of them to let [Lennox] know if he can recollect any expression to have been used in his presence, which could bear the construction put upon it by his Royal Highness, and in such case, by whom the expression was used.

This was sensible, but ineffective, turning up no further clarification of the matter, and leaving Lennox no other option than to challenge York to a duel for suggesting that Lennox was too cowardly to respond to an insult.

Lt. Col. Charles Lennox

[1789]

© Wikipedia

Not surpisingly, there was unconfirmed speculation about the episode. Even before the duel was announced, the Edinburgh Advertiser, for May 19, 1789, suggested that

The cause of this misunderstanding originated some time since, concerning a toast at a public dinner; and, since that, gave rise to the words complained of, which were uttered at the Duchess of Ancaster's masquerade, to a person mistaken by the Duke for the Colonel, and by that person conveyed, of course, to the latter gentleman. (p. 24)

In The Greville Memoirs (Volume 1) published in 1874, an entry dated Dcember 24, 1822 provides some additional clarification from the Duke of York himself that is largely consistent with the account in the Edinburgh Advertiser.

The other day I went to Bushy with the Duke [of York], and as we passed over Wimbledon Common he showed me the spot where he fought his duel with the Duke of Richmond. He then told me the whole story and all the circumstances which led to it, most of which are in print. That which I had never heard before was that at a masquerade three masks insulted the Prince of Wales, when the Duke interfered, desired the one who was most prominent to address himself to him, and added that he suspected him to be an officer in his regiment (meaning Colonel Lennox), and if he was he was a coward and a disgrace to his profession; if he was not the person he took him for, he desired him to unmask, and he would beg his pardon. The three masks were supposed to be Colonel Lennox, the Duke of Gordon, and Lady Charlotte. This did not lead to any immediate consequences, but perhaps indirectly contributed to what followed. The Duke never found out whether the masks were the people he suspected.

If the person insulting Lennox was the Duke of York himself that would explain why he would involve himself so particularly in this business. And it would also explain the otherwise odd detail in the Edinburgh Advertiser account. As reported there, when Lennox tried to get the Duke to explain who could have uttered the words that should have caused him such offense,

the Duke replied very gallantly, "I beg, Sir, that you may not consider my rank, either as your Colonel, or as a Prince, as any obstacle in your way. I wear a brown coat, and every where, but on this parade, wish to be treated as a private gentleman."

Assuming Lennox was the man behind the mask, and that Lennox knew all along that the author of the insult was York, the Duke was, in effect, inviting Lennox to challenge him to a duel as one gentleman to another.

Another account, certainly biased in favor of the Duke, is provided in The Life and Letters of Sir Gilbert Elliot, Volume I in an entry dated May 30, 1789, just a few days after the duel. This account provides some additional context for the dispute and comes closest, perhaps, to the underlying argument of the three Gillray-Aitken prints. In that account, Sir Gilbert notes that Lennox had been "forced into" the Duke's regiment (presumably by the King and Pitt) "without so much as an intimation to the Duke, who was the colonel, against the rules, or at least common practice, of the army." And when the Duke had nonetheless graciously welcomed Lennox to his regiment, Lennox rebuffed this conciliatory overture, saying, "that it was the King's pleasure he should be there, and that was enough for him."

Sir Gilbert also asserts that during the course of the entire winter Lennox had been "amusing himself. . . with abusing and insulting the Prince of Wales and the Duke of York in the most scurrilous and blackguard way, both behind their backs and sometimes to their faces." But "All this winter" would mean the winter of 1788/89, the time of the King's madness and the resulting Regency crisis.

At that time, even within the Royal family itself, there was considerable disgust about the seeming heartlessness of the Princes towards their father. While the King was at a low point in November, they made no secret of their hope of his speedy demise, circulating lists of potential cabinet selections in the expected Whig ministry. And even into the Spring in the months leading up to the appearance of Gillray's prints, the two Princes did little to endear themselves to anyone by their behavior. On April 1st a ball was given in honor of the King's return. According to Robin Reilly, "The Prince of Wales and the Duke of York did not join in this festivity; they allowed their complimentary tickets to be offered for sale in Bond Street." And at the St. George's day service at St. Paul's Cathedral on April 23 with the King in attendance, the two Princes were reported to have behaved "with offensive vulgarity, pointing, talking loudly, guffawing, and according to one account, munching biscuits during the sermon."

A Tory like Lennox, whose uncle was part of the Pitt ministry would certainly have joined in the outcry against the Prince of Wales and by extension against the Duke of York. And the Duke of York would have seen any criticism of his brother, especially from one in his own regiment and from behind the safety of a mask, as cowardly and ungrateful. So the dispute, though it had some personal animus, was fundamentally political.

Sources and Reading

- "Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany," Wikipedia

- "George IV," Wikipedia

- "Charles Lennox, 4th Duke of Richmond," Wikipedia

- "Charles Lennox, 3rd Duke of Richmond," Wikipedia

- The Greville Memoirs

- Life and Letters of Sir Gilbert Elliot,

- Janice Hadlow, A Royal Experiment, New York, 2013, Chapter 11: An Intellectual Malady

- Robin Reilly, William Pitt the Younger, New York, 1978, Ch. 14; The Regency Crisis

- Thomas Wright and Joseph Grego, The Works of James Gillray, the Caricaturist; With the History of His Life and Times, p. 110.

Comments & Corrections

NOTE: Comments and/or corrections are always appreciated. To make that easier, I have included a form below that you can use. I promise never to share any of the info provided without your express permission.