Charon's Boat, or the Ghost's of "all the Talents"

In classical mythology, Charon was the ferryman of the dead, transporting them over the river Styx or Acheron from the land of the living to Hades, the realm of the dead. Guarding the gates of the Underworld was Cerberus, most often depicted as a fierce three headed dog whose job it was to keep the dead from escaping and returning to life.

This wonderfully constructed and amazingly detailed print was likely begun as a prediction of what would happen to the Ministry of All the Talents (aka the Broad Bottom Administration) if they continued to pursue a pro-Catholic agenda, but it ended up as a kind of comprehensive visual epitaph when it was finally published months after the demise of the administration.

© Trustees of the British Museum

As depicted by Gillray, the "Broad-Bottom Packet" is clearly in trouble. The waters are choppy. The yard arm is broken. The main mast symbolizing the Prince Regent's equivocal support is cracking near the top where it begins to form a gold cross surmounted by the princely headdress with the word "Fitz" across it (referring to his unacknowledged Catholic wife, Maria Fitzherbert. And the main sail, appropriately strung with rosary beads, and inscribed with "Catholic Emancipation" is being torn by the winds generated by harpy-like opposition groups including "Cobbett's Letters" from his weekly "Political Register," "Protestant's Letters" from the "Morning Post," and "Damnable Truths" from the radicals Sir Francis Burdett and Horne Tooke. Some supporters, including Sheridan and Thomas Erskine are already sick. Henry Addington has been tossed overboard. Even the naval hero, Earl St. Vincent, manning the tiller, is finding it difficult to steer the boat. He cries "Avast - ! Trim ye Boat! or these damn'd Broad bottom'd Lubbers will overset us all."

He is referring to occupants of the packet as a whole, but in particular to the three members of the Grenville/Temple family who led or were part of the Ministry: Prime Minister William Wyndham Grenville (wearing a Cardinal's hat and holding a chalice) who had resigned with Pitt in 1801 over the King's opposition to Catholic Emancipation; his nephew Earl Temple, dropping notes in the water inscribed with "Stationery " and "Places, Pensions, Sinecures" (see Gillray's 1807 The Fall of Icarus); and Ballast from Stowe (the family seat of the Temple-Grenvilles) which could refer to George Nugent-Temple-Grenville, 1st Marquess of Buckingham (married to a Catholic) or Thomas Grenville, First Lord of the Admiralty in the Ministry of all the Talents.

The epithet "Broad Bottom" generally referred to the broad base of the ministry, pulling from Tories, Whigs, and Independants for cabinet posts. But Gillray used it particularly to satirize the Grenville's ample posteriors.

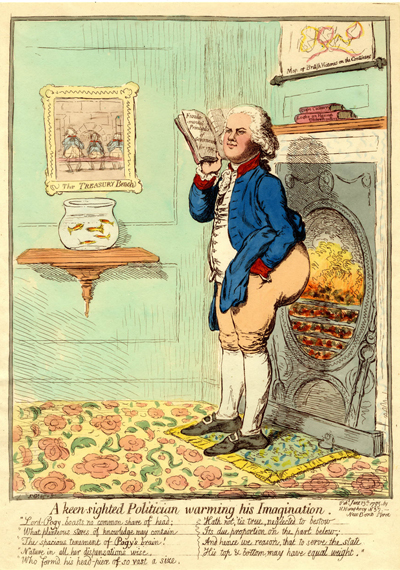

The "Broad Bottomed" William Wyndham Grenville [June 13, 1795]

© Trustees of the British Museum

All of the Grenville-Temples had shown support for Catholic Emancipation over the years and particularly recently, so it is not surprising that the flag of this packet includes the Temple family motto "Templa quam dilecta," which means "How beloved are thy temples!" but also the tiara and triple-barred cross which seems to have been specific to the papacy. And if that were not enough to associate this voyage and its leaders with Popery, the subtitle to the print as a whole implies that it is based on a presumed painting in "the Pope's Gallery at Rome."

The immediate cause for the the troubles being visited upon the packet was the Roman Catholic Army and Navy Service Bill which had been introduced in March, 1807 as a separate measure by Lord Howick (Charles Grey) who is shown as Charon with his punt-pole pushing the craft towards Hades and extinction. The bill sought to allow Catholics to serve in both branches of the military and to remove any hindrances to normal advancement by Catholics (or members of any other religion) within the profession. It was an extension of previous measures supported by Whigs which helps to explain why Howick's punt-pole is labeled "Whig Club" Howick and most members of the Ministry of all the Talents believed that the ongoing war with France provided an obvious reason for allowing as many able-bodied citizens of the United Kingdom to serve and advance in the military—including Catholics. But in spite of the recent monitory example of Pitt, they underestimated the implacability of the King and the depth and breadth of anti-Catholic sentiment in the country at large.

One indication of how the opposition viewed the proposal is suggested by the words given to Howick by Gillray: "Better to Reign in Hell!_ than Serve in Heaven." The words come from no less a rebel than Satan in Paradise Lost (Bk I: 263. If Howick is a kind of rebellious Satan, the enemy of God (and the Anglican Church) it makes sense that he should be poling his way towards a hellish shore populated by such arch revolutionaries as the Irish Arthur O'Quigley and Edward Despard, the Puritan Olver Cromwell, the recently departed Whig leader Charles James Fox, and the author of the French Terror, Maximilien Robbespierre.

Hovering above them in the clouds are George Canning, Perceval or Castlereagh, and Hawkesbury who are portrayed as both witches riding on broomsticks and the three fates destined to cut the lifeline of the Talents and become part of the second Portland ministry.

The print is signed "Js Gillray fect" which sometimes means that Gillray is working from a drawing provided to him by an amateur. But in this case, the only surviving sketch of what became Charon's Boat is clearly by Gillray himself. And though the image is reversed, the basic elements of the print are already there in the rough sketch: the boat full of broad bottoms including one with a bishop's mitre, the standing Charon, the sail with Catholic written on it, the awaiting figure of Charles James Fox on the shore, and a barely visible indication of the three witches above him. Next to Fox but in the foreground, also barely indicated, are the three heads of Cerberus, which Gillray was to move over to the other side in the final print. In the bottom right hand corner, Gillray has written "The Stygian Lake. And on top, he tried out several versions of the title: "Charons Boat Passing(?) the Stygian Lake, or the last voyage of the Broad Bo[ttoms]" and alternatively "the Broad Bottomites on Their Last Voyage.

© Detroit Institute of Arts

This was not the first time Gillray had alluded to the myth of Charon's boat. He used it in a 1788 print, Charon's boat,or Topham's trip, with Hood to Hell. A comparison of the two prints is instructive in several ways.

© Trustees of the British Museum

First, we can see how far Gillray has come in the sophistication of his print-making in twenty years. By 1807 he had a complete repertoire of caricatures of all the major and many of the minor political figures of his time, and he tended to use them more frequently in larger numbers per print. Each face was uniquely caricatured and Gillray could now reproduce that face from any and every perspective. He was not just limited to caricature profiles. In many cases, the figures had a symbol or set of symbols associated with them which could be used as a kind of short hand for identifying them—the alcoholic complexion of Sheridan, the erect posture of Moira, the tankard of Whitbread, and the broad bottom of Grenville.

Next, his command of gesture, perspective, and arrangement of figures in the visual space of the print had immensely improved. The way that the 1807 Charon (Charles Grey) stands with one foot on the gunwale and grips his Whig Club is so much more convincing than the somewhat awkward position and grip of the earlier Charon (Colonel Topham). The broad bottom packet of 1807 is crammed with figures, but none of them (except perhaps the ballast from Stowe) feels contrived. The arrangement is completely convincing. Finally the sense of depth in the 1807 print is immensely enhanced by being framed by the dark rocks that form a cavern into which the boat is being poled.

But the greater detail and sophistication of Gillray's later work came at a price. The first Charon's Boat was the fifth print about the Westminster by-election published within a month of one another, some within days of the actual voting. The second Charon's Boat was published in mid-July of 1807; the Ministry of all the Talents had been dissolved on the last day of March. This huge delay in delivery may be attributed to a decline in Gillray's ability concentrate and make quick decisions. But it may also suggest Gillray's realization that the topicality of his work was no longer as important as it once was. That his customers were no longer buying his prints because he was first to the story, but because his caricatures were simply unparalleled in creativity and artistic finish.

Sources and Reading

- Commentary from the British Museum on Charon's Boat, or the Ghost's of "all the Talents".

- Draper Hill, The Satirical Etchings of James Gillray, 1976, #90

- "Charon," Wikipedia

- "Catholic emancipation," Wikipedia

- "Roman Catholic Relief Bills," Wikipedia

- "Ministry of All the Talents," Wikipedia

- "Henry Addington, 1st Viscount Sidmouth," Wikipedia

- "Francis Burdett," Wikipedia

- "Edward Despard," Wikipedia

- "Edward Law, 1st Baron Ellenborough," Wikipedia

- "William Grenville, 1st Baron Grenville," Wikipedia

- "Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey," Wikipedia

- "Francis Rawdon-Hastings, 1st Marquess of Hastings," Wikipedia

- "Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, 3rd Marquess of Lansdowne," Wikipedia

- "Richard Temple-Nugent-Brydges-Chandos-Grenville, 1st Duke of Buckingham and Chandos," Wikipedia

- "Samuel Whitbread (1764–1815)," Wikipedia

- Thomas Wright and R.H. Evans, Historical and Descriptive Account of the Caricatures of James Gillray #339.

- Thomas Wright and Joseph Grego, The Works of James Gillray, the Caricaturist; With the History of His Life and Times, p. 350.

Comments & Corrections

NOTE: Comments and/or corrections are always appreciated. To make that easier, I have included a form below that you can use. I promise never to share any of the info provided without your express permission.